John Thompson III '88 - Carrying The Torch

2/24/2021

Heading into the 2000-2001 season, the Princeton University men’s basketball team were entering a new era, led by first-year head coach John Thompson III. Selected to finish eighth in the Ivy League preseason poll, significant questions surrounded the team.

All-Ivy League center Chris Young had signed a professional baseball contract and Spencer Gloger, an honorable mention All-Ivy selection had transferred. Ray Robins had taken the year off.

Fortunately for the Tigers, “JTIII” had two Hall of Fame coaching legends – his coach at Princeton, Pete Carril, and his father, John Thompson, Jr. – whose counsel and mentorship served as guideposts that season – and long since his days on the sidelines for the Princeton concluded.

That was probably the best season of my life.John Thompson III

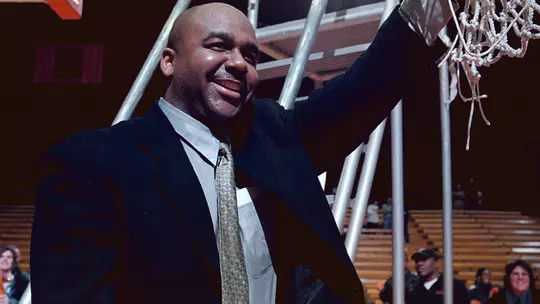

Under Thompson’s tutelage, the Tigers went on to shock the country by winning the Ivy League championship and earning an automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament. Nate Walton was a unanimous first-team All-Ivy selection. Ahmed El-Nokali was second-team All-Ivy and Kyle Wente was named honorable mention All-Ivy League. Konrad Wyoscki was the Ivy League Rookie of the Year. A masterful coaching effort on Thompson's part had gotten the most out of the team, and led his players to believe in themselves when many others wouldn’t.

“Many days we probably did look like the Bad News Bears out there, but we had a group of guys that believed in each other,” said Thompson. “We had a group of guys that believed in me. We had a group that played really well for each other. We ended up winning the league and it was truly special.”

Gatorade showers are typically reserved for the football field or the inside of a locker room. Thompson recalls the team dumping a cooler of Gatorade on him on the court following the last game of the season against Pennsylvania – as students were rushing the court following the Tigers big win over the Quakers. Naturally, the court got slippery while the court was being stormed and it’s the only time Thompson remembers seeing that happen at a basketball game.

Thompson would end winning up three conference titles in four seasons as a head coach of the Tigers, but feelings of self-doubt crept in before he started the job. He recalls stopping by Pete Carril’s house the day he accepted the job, sitting on a chair and thinking to himself that he could handle the X’s and O’s side of being a head coach, but was concerned he wasn’t the type of guy who could have the influence on his player’s lives the way his two mentors did.

“I was worried that I wasn't ready for that,” said Thompson. “Having the opportunity to come back to Princeton and coach was an unbelievable experience.”

There’s not very often a day goes by where he does not hear Carril's or his father’s voice in his head.

After four seasons as head coach at his alma mater, three Ivy League titles and two trips to the NCAA Tournament, JTIII would take his father’s old job at Georgetown University ahead of the 2004-05 season. He led the Hoyas to eight NCAA Tournament appearances, including a run to the Final Four in 2006-07, three Big East regular season titles, one Big East Tournament title and 278 wins – second all-time in school history behind his dad. These days, Thompson leads the athlete development and engagement department with Monumental Sports & Entertainment, the company that owns the Washington Wizards and Washington Mystics.

As important as the wins, the NCAA Tournament appearances and the accolades are, Thompson also views the role of a coach as more than what happens on the court. While he doesn’t view it as strictly social work – you’re not purely there to change lives and help people, and you do need to win games – in doing that you need to have a caring and understanding of the young men and women you are coaching. He sees 17-18 year olds walking in the door with no clue what the real world is all about, even though they think they do.

It’s about getting them to a point where four years later, you can push them out of the nest, they're ready to stand, they're ready to continue to grow and they're ready to start to be leaders in their own right. That is a responsibility of the coach, while you try to figure out how to win games.John Thompson III

Thompson learned so much from his father and Coach Carril about being a man and being a coach. His attitude and philosophy toward coaching has been largely shaped by them.

“It’s just the commitment and dedication as a coach that you need to have to your athletes and the commitment and dedication that you need to have to the school,” said Thompson. “If it is genuine, if they see it, if they feel it, they believe it and it will be reciprocated.”

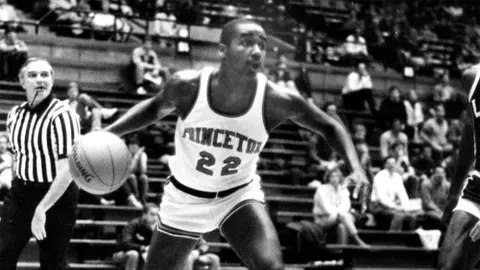

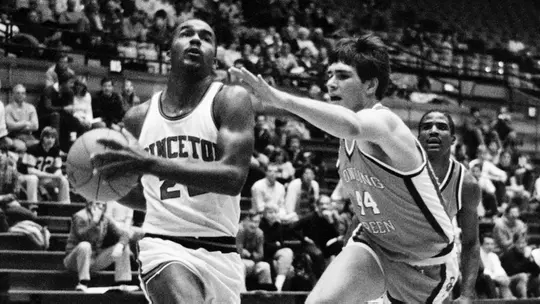

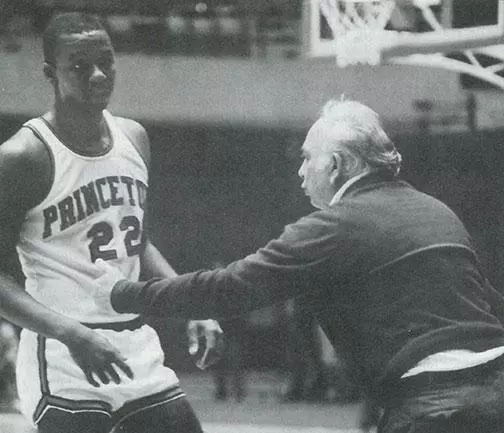

Before getting into coaching, Thompson III played basketball at Princeton. Always wanting to attend a great basketball school with elite academics, Princeton proved to be a natural fit. He recalls his recruiting trip vividly and how Pete Carril was bluntly honest with him about his game. It was Carril’s brutal honesty that not only solidified Princeton as his choice, but also reminded him greatly of his father.

I always say that they were twins, just one was a big Black guy and the other was a little white guy.John Thompson III

“Both of them were brutally honest,” said Thompson. "There's also a true, genuine caring in their own manner about their players and about the institution. There was a true caring that went above and beyond what happens on the court. There was an understanding of the responsibility to have discussions above and beyond basketball. Their deliveries were very similar.”

Thompson’s first two years as a Tiger were not easy. That honesty, which attracted him to Carril and Princeton, was hard to deal with at times. He recalls calling his father to vent about Carril’s critiques of his game.

“He said ‘that man knows more about basketball than you will ever know. Do everything he tells you, don't ever call here again complaining about him.’ Then he hung up on me.”

Thompson took Carril’s advice and improved on his weaknesses, resulting in a fantastic final two years at Princeton. He ended his career fifth all-time in school history in assists with 347 and had two seasons with over 100 assists; he handed out 112 in 1986-87 and 108 in 1987-88.

“I started to grow up and realize that most of what Coach was saying was accurate,” said Thompson. “It quickly went from me not enjoying my experience to me absolutely loving my experience. It quickly went from me being frustrated and early on not really liking Coach, to me loving Coach. I had to grow up, I had to mature, I had to understand that I didn't know everything. As my dad said, he knows more basketball than I'll ever know.”

Off the court, Thompson loved Princeton from the start and would do it all over in a heartbeat. He met his wife and best friends there while going through a true maturation process.

In August 2020, his father passed away. It was a crushing blow for Thompson and his family but it was also a monumental loss for the basketball world. Coaches around the country began wearing his trademark towel over their shoulders while coaching and tributes for “Big John” poured in from far and wide.

Known for his willingness to speak out when he saw injustice, “Big John” once famously walked off the floor and refused to coach in protest of the NCAA’s Proposition 48, which prohibited scholarship student-athletes from playing as a freshman if they did not qualify academically. He felt the minimum score requirements on entrance exams were biased against poor students. Thompson notes his dad was encouraged by what he saw from athletes over the past few years, particularly this past summer.

One of the things at the end that made him extremely proud was to see athletes, Black and white, starting to be willing to take a stand.John Thompson III

“Athletes being willing to use their voice and use their platform, understanding that they can make a difference, that they can cause change in this world. For so many years, athletes, players, coaches and administrators were afraid to do that. They didn't want to didn't want to take the risk. That's something that he never had a problem doing.”

Often out on a limb by himself, it was evident more athletes had followed the elder Thompson's lead. JTIII himself completely agrees that athletes do have the power to enact change is glad to see today’s athletes begin to carry on his father’s legacy.

“Athletes have a voice, have a platform, have an audience and have a following,” said Thompson. “That can at least spark and start discussion. For there to be change, we need that to continue to happen more regularly. We need to push the envelope. We need to have staying power in that you can't have the summer that we just had and then it just goes away.”

Thompson feels that it’s sad we have to designate a special month to acknowledge the accomplishments of Black people, as opposed to it being more ingrained in society and education as a whole. That being said, he also recognizes it is a time where we do make a conscious effort as a nation to recognize the accomplishments of Black people and how they have positively affected the country and the world.

“It’s extremely important that we continue to make a conscious effort to educate ourselves and push towards economic empowerment in our communities,” said Thompson. “We need to continue to support Black owned businesses so that can happen. We need to continue to work towards, from a fiscal point of view, closing the gap and gaining ground.”

While Thompson continues to continue his father’s legacy in Washington D.C., Princeton will always be home to him. Along with meeting his wife there, two of his three kids were born there.

“I said in my press conference when I left Princeton for Georgetown, that I'm one of the few people on earth that's fortunate enough to leave home yet still come home,” proclaimed Thompson. “My youngest, who never lived in Princeton but was born there right when we're moving still says Princeton's home to him.

It’s a special place. It's a special community. Being part of Princeton basketball, I think most people that have gone through the program from Butch van Breda Koff through Mitch Henderson will say that experience changed and shaped their lives. That is true for me, I know it is true for most of my teammates and it’s is probably true for at least a few of the people that I coached when I was there.”