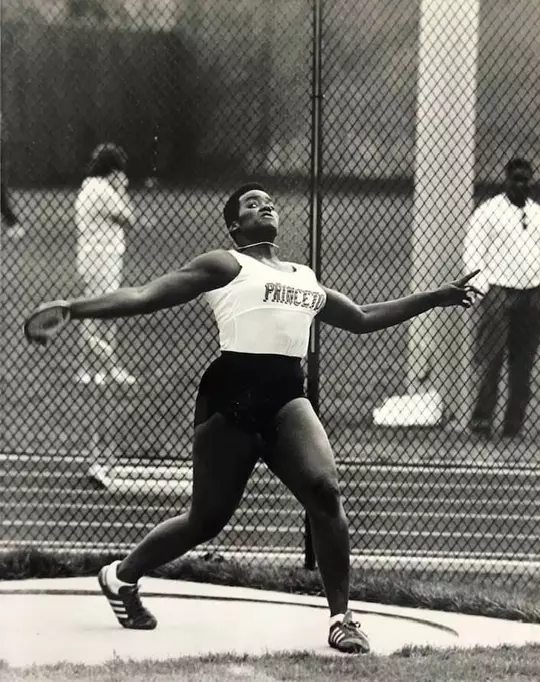

Deborah Saint-Phard '87 - All-American, Olympian, & Physician

2/10/2021

When Deborah Saint-Phard was six months old, her family was forced to flee her native Haiti, one step ahead of dictator Papa Doc’s killer regime. Her father was on a disappearing list, as it was known, destined to be taken and “disappear,” never to be heard from again.

It wasn’t until their flight had landed in Miami that her family felt safe, she would be told later. Flights known to have people trying to avoid the lists were ordered turned around in mid-air.

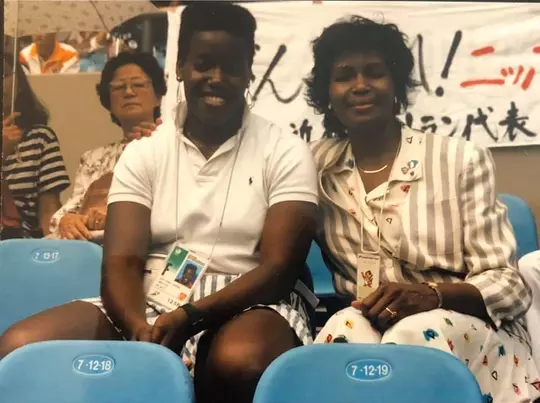

It was a little more than 20 years later when Saint-Phard, a shot putter, walked through a tunnel and out into the Olympic Stadium in Seoul, South Korea, as the flag-bearer at the 1988 Olympic Games for her native country.

“We were on a back practice track for a few hours,” she says. “All of the athletes were just milling around, so we got to see the athletes from all the other countries. It was great. We had pictures with all kinds of people. African men. Italians in fancy suits. Finally it was time for us to march in. We were in full dress. I grabbed the flag and walked through the darkness where it was very quiet. Suddenly, we were out on the stadium track and there were 85,000 people there, screaming our names, clapping. It was overwhelming.”

She laughs when she talks about how she was chosen to carry the flag in the first place.

Our entire delegation was a tennis player, a sprinter, a marathon runner and three officials. That was it. They looked at me and said I should carry the flag. I asked why, and they said it was because I was the strongest one there. And that’s how I became the flag bearer.Deborah Saint-Phard

Today she is in Colorado, where she works as a physician who specializes in promoting girls’ and women’s health. She’s come quite far, literally and figuratively, from that night when she was six months old and her family had to flee from a homicidal dictator.

The arrival in Florida was her introduction to the United States. If she doesn’t remember Miami, she remembers the other stops between there and when she came to Princeton 18 years later – and there were all kinds of other stops.

Let’s see. It was Florida to New York City to Kansas (Topeka, where she was asked why she “looked black but talked white”) to Maryland (Columbia, then Chevy Chase). From there it was back to Kansas, this time for a year and half in Wichita. Then it was to the South for high school, the first two years in Mobile, Ala., and then to Slidell, outside of New Orleans for 11th and 12th grades.

Her parents were training as psychiatrists, and the travel came from where their work took them.

My parents were all about God, family and education. Those were the priorities. They didn’t lead with athletics.Deborah Saint-Phard

When she was 12, her parents separated, and she and her brother and sister would live with her father after that, spending a month in the summer with her mother.

She played soccer as a kid, and by junior high she played volleyball, softball and basketball. It was in Wichita that she wanted to try out for the track team.

“I thought I was fast,” she says. “The coach put me against the other girls, and I ran. Then he came over and said ‘why don’t you try the shot put’ and pointed ‘over there.’ I wanted to be a sprinter, but I found out that ‘over there’ meant a big metal ball.”

Her father relocated yet again for work, this time to Alabama, when she started high school. Then it was off to Slidell High School two years later, and she played on the basketball team there. When her dad wanted to move one more time a year later, she instead stayed with a family she’d babysat for, while her brother, Sam, a soccer player who’d play at Centenary College and then Longwood, moved in down the street.

Her sister had sickle cell, which led to a stroke when she was 14. After that, she moved back to live with their mother.

Saint-Phard’s basketball team was really good, but it was in track and field where she really began to assert herself. Her goal by the time she was a junior was to win the state championship.

“And then I choked,” she said. “I doubt it even went one foot. I remember sitting on the side of a hill, sobbing. I’m talking chest-heaving sobs. Through all the tears, I told my coach I was going to win this the next year. I felt utter disappointment and frustration.”

The winner that year was a girl named Lila Knox, from Capital High School in Baton Rouge. Saint-Phard’s father advised her to study Knox, and beating Knox became her obsession. As a senior, she played volleyball, basketball and softball, and she also won the discus and shot put state championships, beating Lila Knox in the process.

“She had no idea who I was,” Saint-Phard says.

When it came time to choose a college, she thought she’d head to a state school, possibly LSU. She also applied early to Brown and got in, but then her mom suggested Princeton. Even though it was after the deadline, she applied and got in.

“I wasn’t recruited by anyone for athletics,” she says. “And I wasn’t looking to do athletics in college. I didn’t think I was that good. But I got calls from Bob Malakoff, the soccer coach, and Peter Farrell, the track and field coach.”

She arrived on campus in the fall of 1983. She’d do both sports as a freshman, including being a part of an NCAA tournament soccer team.

She qualified for the indoor and outdoor NCAA championships as a junior. By her senior year, working a great deal with men’s coach Fred Samara, she set as her goal to be an All-American, which meant finishing in the top six.

“I was in fourth place with one throw left,” says Saint-Phard, the team captain her senior year. “It was my last college throw. I was already an All-American. I didn’t have a care in the world. I look up and Fred is running to me. He was so excited. He told me that the last throw was a personal best and qualified me for the World Championships.”

Samara was both her physical coach and mental guru.

I remember being with Fred, drilling and drilling and throwing and throwing and drilling and drilling and throwing and throwing. There was always something, a finger, a hip, an arm. I would ask him when I was going to get it right, and he said I’d know and it would be effortless. And he was right. That last throw was effortless.Deborah Saint Phard

Meanwhile, there were political events back in her native country that would have a major impact on her athletic career. Francois Duvalier, known as “Papa Doc,” the “President for Life” who stayed that way by killing off his political opponents, was replaced in 1971 by his son Jean-Claude, known as “Baby Doc.” It would be 15 years later when Baby Doc was finally forced into exile, freeing the island nation from the dictators who had held the country.

Saint-Phard’s father would become the Haitian ambassador to the United Nations. Saint-Phard would have the door open for a chance to compete in the Olympic Games.

She would take fourth place at the 1987 Pan Am Games. Then she’d choose Temple over George Washington for medical school, partly because the start date for school meant she could compete at the World Championships.

“I asked Fred what I could do in med school,” she says. “He told me to take tai-kwon-do.

I became a blue belt. When you’re punching, it’s straight. I had a habit of over-rotating my throws in the shot. I was getting the same instruction from tai kwon do instructor that I’d hear from Fred. Punch, and turn through your hips. Fred has this ability to have a true and complete understanding of his athletes. Fred knew me as a person and an athlete. He’d say you have to learn to listen to your body. The life lessons through sports that I learned then are still lessons I use today. Self-care. Self-compassion, so you can provide care and compassion to your patients. Fred would tell me ‘you can take off three days now or you can take off three weeks or three months off if you don’t listen to what your body is telling you.’”

She’d finish 18th at the World Championships in 1987 and then 19th at the Olympic Games in Seoul.

“Being at the Olympics? It was like camp,” she says. “It was like a camp with the best athletes from all around the world.”

“I’m on the physical medicine side,” says Saint-Phard. “I think it was a part of me. I still think like an athlete. When I was in college, I wished that there was as greater balance and equity between men and women in health care. That’s been achieved now. Part of going into women’s sports medicine, I wanted women and girls to have the expertise from professional women and not just men who were orthopedic specialists."

I hear from my women and girl athletes that whatever their concern is wasn’t being taken seriously. She’s a ballet dancer, not a football player. That was my calling. I wanted to become the best women’s sports medicine doctor I could.Deborah Saint-Phard