Book Excerpt - The First 50 Years Of Women's Athletics: Vietta Johnson

3/18/2021

As part of the celebration of the first 50 years of women's athletics at Princeton, goprincetontigers.com/50Years will be featuring monthly excerpts from the book that Department of Athletics historian Jerry Price is writing about the evolution of the program from 1970 through 2020.

Vietta Johnson’s introduction to the sport of running did not come on a track.

Nope. It came when she’d get off the school bus as a kid, in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn.

“I was running away from the young men in the gangs,” she says. “They were trying to steal our bus passes. I outran them. They never caught me.”

Her father was a chemistry professor at Long Island University. Her mother was in education as well, rising eventually to be the Deputy Superintendent of the New York City public schools and then ultimately the Superintendent of the public schools in Chicago. When she was a kid, though, the family lived in LIU campus housing, which consisted of three buildings.

“The Fort Greene projects were at the corner from where we lived,” she says. “You didn’t go through Fort Greene Park back then. The odds of getting out weren’t in your favor.”

It doesn’t take more than about 30 seconds or so of talking to Vietta Johnson to realize that she is someone very special. She runs the full range of emotions minute by minute, and she has no capacity to conceal what she feels about whatever the subject of the moment is.

She is smart, driven, loyal and brutally honest. She is tough and humble. She laughs and then cries and then laughs again, doing both at the same time when she talks about how her grandmother, a sharecropper and the daughter of a sharecropper, just turned 100.

She is thoughtful, as in a deep, considered thinker, and she is thoughtful, as in someone who cares very much about the people she meets along her way. She talks quickly, but in a controlled way, knowing full well what she is saying at all times. She isn’t rambling at all. Nor is she preaching. She is simply “being Vietta,” as more than one of her Princeton classmates says about her.

Mostly what is clear, beyond all of that, is that this woman is not going to in any way BS you. She speaks directly at all times, and even more than that, she speaks directly from her heart at all times.

And the story that she tells is incredible.

It starts out with the gang members on her block. It continues through the No. 1 public high school in New York City, Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan, where she first tested into and then became a star as a runner and a student.

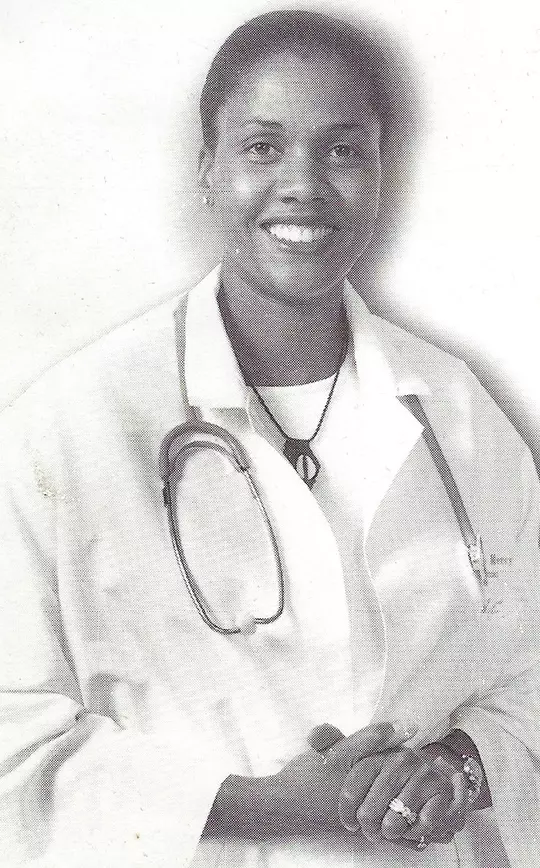

From there it was on to Princeton, Class of 1982, where she also was a key contributor to the early women’s track and field powerhouse of the late 1970s and early 1980s, not to mention a hard worker and entrepreneur. Her next stop was Harvard Medical School.

Today she is an orthopedic surgeon in Chicago – “I’m a New Yorker through and through. I just live in Chicago, but I’m a New Yorker,” she says – and she had to go through what essentially was a living hell of a residency to get there. When she finally finished all of the slights she had endure along the way, she became just the 10th black woman in the United States to become an orthopedic surgeon. She has spent her career treating patients in underserved communities.

You think you can do all of those things without being tough?

“I think we all need to meet people on a human level,” she says. “People are human. We all bleed the same.”

This is a woman who started out in life running way from gang members in Brooklyn, until she decided one day that she wasn’t going to run anymore. So what did she do? She met the leader of the gang on a human level.

His name was Ronald, but everyone called him “Half-Head,” because he had been burned early on in his life and had hair on only half of his scalp. He did not like the nickname. How did she find that out?

“I was tired of running from them,” she says. “One day, I saw him coming and I said ‘I’m not running anymore.’ So I talked to him. He said he hated being called ‘Half-Head.’ So I called him ‘Ronald’ after that. He was a smart young man, nice as could be. After that, I didn’t have to run anymore.”

Well, not from the gang kids anyway. There would be other hurdles, some of which were literal and some of which were figurative.

All of her running had made it clear that she was fast. At Stuyvesant, she found track coach Persio Cappellan, who would pile his star runners into his car and drive them to the top meets in the New York City area and beyond, as the Stuyvesant relay team qualified for the first Penn Relays for high school girls, in 1976.

It was there that she first caught the eye of Peter Farrell, who was then in the early stages of coaching the women’s track and field program at Princeton. Farrell himself was a veteran of the New York high school running scene, first as an athlete at Archbishop Molloy and then as the girls coach at Christ The King.

“I love her to death,” Farrell says. “She was a tough kid from Brooklyn. She worked extremely hard, stayed late every day as she, I’m pretty sure, spent a lot of time in labs. On a personal note, I found out after my farewell dinner that she called her office saying she was closing early to catch a plane from Chicago to Princeton and needed details of the dinner location. She stayed after the speeches, walked up to me and my family and said ‘Peter Do you remember me?’ I was actually stunned, standing with my wife and two daughters. I answered ‘of course I do. How could I forget Vietta Johnson of Stuyvesant High School.’ I have to say of all the returnees from faraway places that night, Vietta was my biggest surprise.”

Johnson was not recruited by Farrell at a time when recruiting for women was in its infancy. She applied and was accepted, and when Farrell saw her name on the admitted students list, only then did he reach out to her. Actually, she applied and was accepted to five Ivy League schools, as well as a few others, including Duke.

“I remember when Peter called me,” Johnson says. “I told him I was very interested in Princeton and very interested in running. Princeton was the No. 1 undergraduate school. Why would I want to go to the people who were trying to be like Princeton when I could go to Princeton. Being a city girl, I wanted to go to one of those beautiful rolling campuses you see on television.”

At Princeton, she was a sprinter and a hurdler, a part of Ivy League Heptagonal championships as a freshman, sophomore and junior outdoors, with a best individual finish a third-place in the 100 hurdles as a sophomore. There was no indoor Heps for the women until her junior year, but Princeton won that one and the one her senior year as well. Princeton would win outdoor Heps her senior year, but she wouldn’t be a part of it after a career-ending ankle injury she suffered while practicing the hurdles.

“I’m such a team player,” she says. “In track and field, you have to be out there yourself, but it’s also a team sport. The people I remember most from Princeton are the people from the track team. I loved it. We were academics. We’d go to a meet and everyone would have their books out. We had work to do. We had our fun on campus and we had our parties, but we were very focused. I know I was.

“We had such great camaraderie on the team. The distance runners were out running six to 10 miles a day. We’d run 100 yards and say ‘let’s rest. That’s enough.’ Sprinters’ lives are different. But we were all the same team. My Princeton experience would not have been anywhere near as wonderful as it was had I not been on that team.”

There was a great deal more to her Princeton experience than just school and running. There was work, and a lot of it.

She worked for food services in Forbes, with omelettes her specialty. She also worked concessions at athletic events, including counting up the money after games and often taking the cash to the bank.

“I worked with such wonderful people,” she says. “My hours in the day were slim. I stayed up many a night. I worked in the kitchen, and sometimes people weren’t as kind to the people who worked in the kitchen as they should have been. Some people would look at me and say ‘you have to work in food services?’ I said ‘if that’s what it takes for me to be here, so be it.’ It also gave me a chance to meet some great people. Those were some good times. It was when I got to step back from school and just be a person.”

She laughs as she tells the story of the time the big dishwasher broke down. What did she do?

“I said ‘we can’t be here all night washing dishes,’” she laughs. “So I fixed it. I’m very mechanically oriented. My mother would have fixed it. She could fix anything. So I fixed it.”

She came to Princeton to be a doctor, something she wanted going back even to high school. This time, unlike when she was choosing an undergraduate school, she was happy to be back in the city.

“Medical school was very challenging,” she says. “I like to tell people that in medical school, I slept ‘sometimes.’”

When she graduated from Harvard, her challenges were just beginning. She had no idea what would be in store for her once she started her residency. It wasn’t something that many people would have been able to handle.

“The toll was great,” she says. “My residency was hell. I was fighting the men. I was the first black person in the department, male or female. It was challenging.”

She was greeted initially by one resident who told her that “women have no place in orthopedics. Women are fun to be with.”

There was more than that. Much more.

“That same man threw hamburgers at me,” she says. “One chief resident made sexually threatening comments to me. One called me ‘Brown Sugar.’ One day a nurse called me upstairs and was in tears. She was distraught. She was shaking. She was a black woman, and she asked me why he would call me ‘Brown Sugar.’ I said it was because he didn’t know me any better. She left distraught.”

They even called her “Miss Johnson” instead of “Dr. Johnson.” So how did she react? How do you think she reacted?

“I told them ‘I ran away from gang kids, but I’m not running away from you,’” she says. “I wasn’t backing down. I come from a family of sharecroppers. My parents went to college, they went to HBCUs [Historically Black Colleges and Universities] and wanted me to go to even better colleges and I did that. Damned if I was going to let them get rid of me.”

She went to see lawyer, who prepared a letter for her threatening legal action. She didn’t to use the letter, but she said that if there was a third strike, she was going to have no choice.

“This is what I have lived first-hand,” she says. “I gave them the letter. I went to the chief resident, and his wife was his secretary at the time. His wife told him that he had no excuse, that I’d been coming to telling them the things that they were doing to me for over a year and they’d done nothing.”

Eventually, two years into her five-year surgical residency, which started after one year of general residency, it started to calm down for her.

When she finished, her first job was in Queens, part of the Mt. Sinai Hospital. She made her way to Chicago with her mother, and she left private practice to work in areas that desperately needed her help, including the South Side and in an area called Englewood, which is known as “Chi-raq.” Around 90 percent of the people she treats are on public assistance.

She also recently started a black women’s orthopedic surgery group.

“I have met women who came up behind me who said that I was an inspiration to them,” she says. “There nothing greater than that. These women who have come behind me look at us as paving the way. I have one of the more horrendous stories. I have fought for women and people of color to give us a chance. Let us show we can do this. We are absolutely capable. I helped usher in two black men behind me. I promised them that nothing that happened to me would happen to them.”

Her story is one of determination, with nothing handed to her along the way. She is one of the great women who have come through Princeton Athletics in its first 50 years.

“The whole thing has made me a more sensitive person,” she says. “I learned how to be far different in my approach. I’m not going to let things slide when I see injustice. I’m going to fight it. Today I can counsel others But it was Princeton that prepared me for this kind of thing, from my injuries to all the hard work. I absolutely loved Princeton, and I loved being part of the women’s track and field team.”