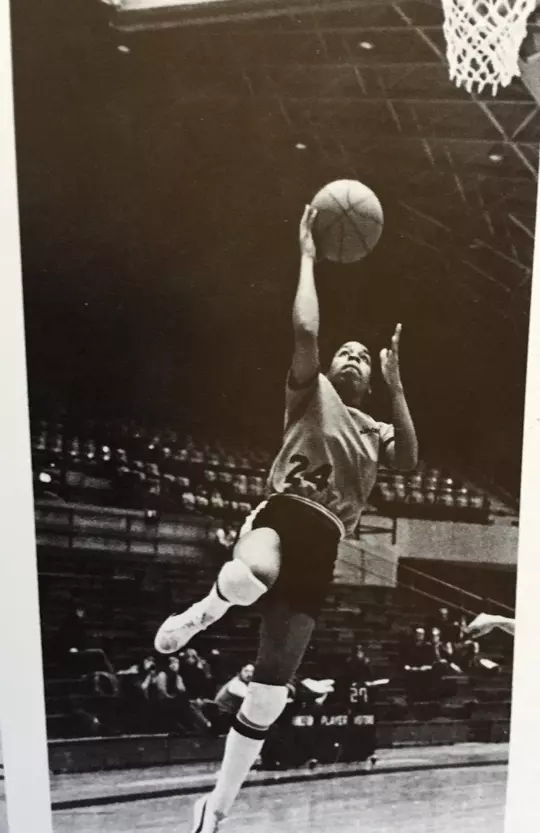

Jackie Jackson '78 - Princeton Pioneer

2/4/2021

There are only three players in the history of Princeton women’s basketball who finished their careers having averaged at least 14.5 points and 7.5 rebounds per game. Only three.

The most recent two are, not surprisingly, Niveen Rasheed and Bella Alarie. Between the two of them, there are five Ivy League Player of the Year Awards and seven first-team All-Ivy League selections, numbers that almost surely would have increased by one each had Rasheed not missed the entire Ivy League season her sophomore year with a knee injury.

The third member of the club was actually the charter member.

She played well before Rasheed and Alarie started lighting up Jadwin Gym and taking Princeton to NCAA tournaments and the national rankings.

For that matter, she played before either of them was even born.

Her name is Jackie Jackson.

Today she lives in Florida, a far cry from her younger days in the northwestern Pennsylvania town of Meadville, between Pittsburgh and Erie. She has not traveled a straight line from the stern winter weather of those middle school and high school days to the current warmth of the Sunshine State, far from it.

In fact, she spent a few decades traveling everywhere and anywhere, often visiting areas that were not quite five-star locations.

“I was a missionary for 26 years,” she says.

It was a life that took her into places that desperately needed her help. It was a constant struggle to make an immediate impact on lives that most definitely needed impacting.

“We did a lot of international travel,” she says. “I was working with pastors and churches in underdeveloped countries. I enjoyed the exposure to the different cultures. I loved being on the ground with the different people. South Africa was the most interesting. Some of that was from being a history major, I suppose. I interacted with a white South African of British descent and a Black pastor and heard their stories of getting through apartheid. And I saw the poverty, and what they were trying to bring to the people there. And I felt the hospitality, despite their poverty. The goals were different wherever we went. We worked with pastors and asked them what their vision was for their village or community."

How could we help? Maybe we could build a church building. Or a school. Or find medical teams. Or set up a women’s conference. My role was to lead the team and facilitate logistics.Jackie Jackson

She came to Princeton in the fall of 1974, when the women’s basketball program was about to start its fourth season. The first three years had seen the Tigers go a combined 15-13, which is more fascinating for the low number of games played each year as much as the record.

By the time she graduated, she had helped the Tigers to an overall record of 63-22, as well as the first four Ivy League championships.

In her senior year of 1977-78, she became the first Black woman to serve as a team captain for any Princeton sport.

She’d also share the 1978 von Kienbusch Award with her teammate Margaret Meier.

In her time at Princeton, the league champion was determined by a tournament, and not even a season-ending one. In fact, the first one saw all six Ivy women’s teams at the time play five games in a two-day stretch.

Still, for Jackson and her peers, the opportunity to play is what mattered.

“Being part of the basketball team gave me a connection and made it easier to meet people,” she says. “Even before practices started, I’d go to Dillon Gym and play in pickup games. I couldn’t wait for practice to start."

For me, basketball was one of the things that helped me feel comfortable at Princeton. It was my first time away from home. Basketball made the transition a lot easier for me.Jackie Jackson

She was actually the second member of her family to attend Princeton, which had been recommended to her by her older brother, himself a member of the Class of 1974. He was the one who had encouraged her to apply. She was interested, especially since there was a women’s basketball team, albeit a fledgling one.

She’d grown up playing pretty much any sport there was with her brother and his friends. She’d eventually play organized basketball, softball and volleyball and ran track.

By the mid-1970s the women’s basketball team had moved over from practicing and playing in Dillon to having Jadwin as the home court, though there were still some games played on the side courts.

Still, the early women’s basketball teams traveled to their away games in glorified station wagons, with the coaches or even the players at the wheel. They didn’t have fancy uniforms, instead buying shirts and ironing on numbers at times.

“It was still so early in the history of women’s sports at Princeton, and it was all fairly new,” she says. “We were a strong, tight-knit community. We were very young. We had limited resources. There was a small percentage of women athletes compared to the overall student body. Maybe women weren’t taken quite as seriously yet. I injured my knee halfway through my freshman year. I got hurt in December. I didn’t have the surgery until April. Maybe it would have been dealt with quicker had I been a men’s player.”

For Jackson, her experience at Princeton was as a Black woman athlete, of which there had been very, very few before her. For this, she relied on what she remembered from Meadville.

“For me, it was the type of environment I’d grown up in,” she says. “I was typically the only Black person in all of my classes in high school, and Princeton wasn’t much different. And just as in high school, it was sports that gave me an acceptance. It was different being an athlete as opposed to one of the students. I never really gave race a thought."

I think that points to the acceptance of my teammates and classmates and how I was judged based on my abilities and performance.Jackie Jackson

The modern era of Princeton women’s basketball, led by superstar players like Rasheed and Alarie, has grown far beyond what the program was in the 1970s. The women’s team routinely draws a large crowd at Jadwin, one that appeals to a male audience that has come to appreciate the ferocity, tenacity and beauty of the women’s game.

This has not been lost on Jackson and her contemporaries.

“Everything has gotten more sophisticated,” Jackson says. “The coaches. All that goes into the training. Prepping. Equipment. That’s reflected in the performance.”

The modern teams have done a great job of connecting with the pioneers from the 1970s, drawing that group of alums back in and sharing their successes with them. Alumni events each year are well-attended and have the feel of a family reunion. In fact, it was through one such even that she was able to reconnect with Meier a few years ago.

“I was talking with Maggie, and we were saying how amazing it would have been to have what they have now,” she says laughing.

But really, I just loved basketball. I’m just grateful I had the opportunity to play.Jackie Jackson