Princeton University Athletics

The First 50 Years Of Women's Athletics At Princeton - An Excerpt From Chapter 1

October 15, 2020 | General

As part of the celebration of the first 50 years of women's athletics at Princeton, goprincetontigers.com/50Years will be featuring monthly excerpts from the book that Department of Athletics historian Jerry Price is writing about the evolution of the program from 1970 through 2020. The book will be available in the spring of 2021, and here is the first of the excerpts, from a piece of Chapter 1:

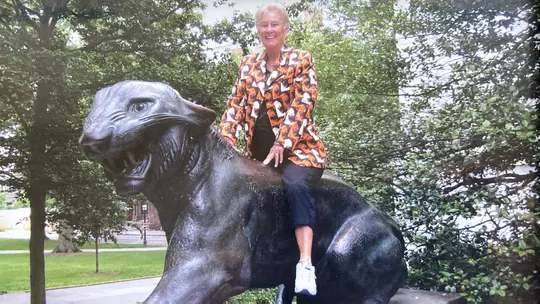

From Chapter 1 – The Builder

When Merrily Dean Baker walked into her office in Dillon Gym on her first day at Princeton in the fall of 1970, she was greeted with a desk, a telephone and a committee report about how women’s athletics were supposed to be implemented at Princeton.

She was almost 28 years old. Her resume included one year at Franklin & Marshall, where she’d also started the women’s athletics program. She’d been called by Princeton University for advice on how to start the program there with the advent of co-education, and she ended up taking the job herself, mostly, she jokes, because at F&M she had to live in the dorms.

Now she was at Princeton, a college founded in 1746. The men’s intercollegiate athletic program was 106 years old on the day she arrived, dating back to a baseball game in 1864 against Williams College. Princeton would play five years later in the first college football game, on Nov. 6, 1869.

There were eight varsity men’s teams by the year 1900. There would be five more added in the next decade, and there would be four more added by World War II.

And now, for the first time ever, there would be women at the school.

“I had no budget and no coaches,” she said. “All I had was this five-year plan. It said that women would be incorporated into existing physical education classes, which was a requirement at the time. Then, after two or three years, they’d be allowed to do intramurals. Then after five, they could have intercollegiate teams.”

She enrolled women in the phys ed classes on the first day, and she personally administered swim tests, which were also required at the time. Next up was Cane Spree, which back then was a very big competition between the freshman and sophomore classes.

“The intramural director at the time came in and said that all these girls were signing up for Cane Spree,” she laughs. “He said ‘we can’t do that. You have to take your shirt off when you lose.’ So I thought for a second and said ‘give them two shirts then.’”

That was the second week.

“People would give me a million reasons why things couldn’t work,” she said. “I would give them a million reasons why it could.”

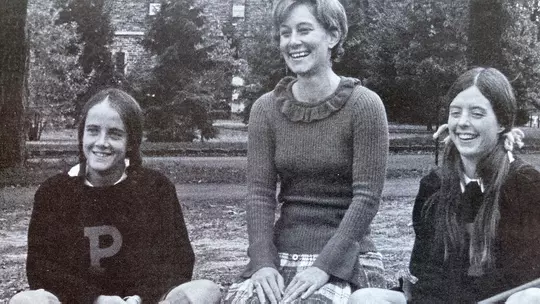

The first time women competed in an intercollegiate event under the Princeton name was not that much later. It began when Margie Gengler and Helena Novakova came into her office and asked if they could play for Princeton at the upcoming Eastern Intercollegiate Championships for women’s tennis in New Paltz, N.Y.

“I went to the bookstore and I bought two Princeton shirts,” Baker says, "and then I took them home and ironed their names on the back. Margie won the singles title, and Helena came in third. Together they won the doubles. They came home with the team trophy as well.

“It wasn’t just a competition,” Baker says. “It was a competition in which Princeton was extremely successful.”

That event was where women’s athletics at Princeton was born.

“Those two women’s tennis players set the tone for everything,” says Royce Flippin, who became the Director of Athletics in 1973.

“I got rid of the five-year plan,” Baker says.

Considering that the original 250 women would all have graduated within five years, it wasn’t surprising that she had to do things on the fly.

“The original women of Princeton reminded me a little of some of the girls I had taught in Turkey,” she says. “They were both bright, an elite group of talented young people. They were being given the opportunity of a lifetime, and they wanted the fullest experience. They weren’t willing to wait five years for athletics.”

She asked one established men’s coach to help her start a women’s team.

“He told me ‘over my dead body will women compete in my venue,’” she says.

“I looked him right in the eye and told him I didn’t come there for his permission. I came for his help.”

Yes, she had to face some of those attitudes and a reluctance to having women at the school, especially as athletes, though she was surprised by how much support she got from Princeton’s alums.

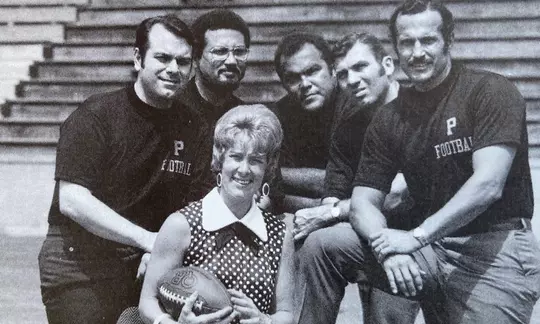

“I was coaching the field hockey team,” she says. “I thought it would be smart to have our games on the mornings of football games against the team the football team was playing. That’s how they did it with a lot of sports. One day we were playing Yale in football, and the PA announcer read off all of the scores from the day and it was ‘Yale, Yale, Yale.’ Then he announced the field hockey final score, and it was Princeton 3, Yale 2, and this great ovation went up. It was the first recognition we’d gotten. When we were walking out of the stadium, I heard some old alums talking and one said to the other ‘we should just put the girls in the stadium at 2 on Saturday.’”

That was more than just a funny one-off line though.

“We became normal very quickly because we were competitively successful,” she says. “I learned very quickly that the men who had doubts lost their doubts after the women started to win games and championships.”

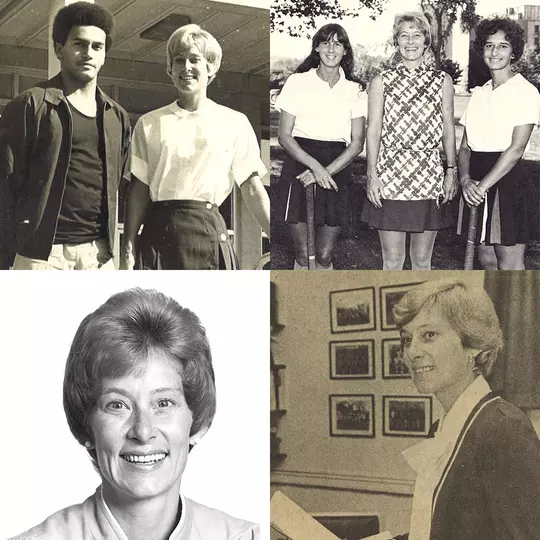

She was a one-woman athletic department in a lot of ways, and more than once she mentions that she thinks of those days of “having raised my fourth child.” She was the administrator. She was the equipment manager. She was the athletic trainer – “I took basically every science there was in college. One day we had a field hockey game against Trenton State (now the College of New Jersey) and one of our girls ran into of one of their players, and her two front teeth were stuck in the other girl's forehead. That got messy.”

She wrote the postgame stories and hand delivered them to the newspapers.

She was also an ambassador for women’s athletics. Princeton sent her around the country to speak to alumni groups, and she was able to connect them with what was going on with the first generation of women athletes.

“I went all over,” she says. “I remember being in the Princeton Club in New York. They sent me there to talk, and there was a sign in the bar that said women weren’t allowed. I mean, I’m there to speak, but there’s a sign that says no women are allowed past this point. This was in 1970. So what happened? One of the men picked me up and carried me across.

“The alumni like bragging rights. They like winners. They got that from the women. Their acceptance would have been a lot slower if they weren’t winning. Then they would have been looked at as a drain on resources.”

Not that there was a lot of money as it was.

“The biggest challenge was developing the resources,” she says. “Because we were on a five-year plan, the University didn’t think they needed to worry about extra money until Year 5. They’d absorb women into existing budgets for intramurals and phys ed.”

What she had working for her was the support of the first two Directors of Athletics, Ken Fairman, who left in 1972, and then Flippin.

“Ken was a wonderful man,” she says. “He was an architect. He told me to develop women’s athletics as I saw fit. He put no constraints on me. Royce felt the same way. It was extraordinary in that day and age to have that kind of support.”

She had more than that though. She also had her own personal drive, her sense of fairness – and the group of women who just happened to be there with her.

“We had the right people in the right place at the right time,” she says. “It wasn’t always easy. I felt like I had to keep a balance between the women, who sometimes thought I wasn’t moving fast enough, and the University, whose head was spinning by how fast we were moving. It worked for one reason.”

Which was?

“It worked because the Princeton women were successful in everything they did. We were lucky. I honestly believe the success of women’s athletics had a major impact on the success of co-education in general.”