Princeton University Athletics

Feature Story: Gia Fruscione ’00 Wants To "Let Her Play"

October 06, 2022 | General

For more information on “Let Her Play” and to register for the free event at Princeton's women's soccer game Saturday, Oct. 8, at 1pm at Roberts Stadium, click HERE.

Gia Fruscione is sitting still, and the uniqueness of the moment tells you a great deal of what you need to know about her.

She’s definitely not the “let me take it easy for a while” type. She’s always on the go.

It’s how she’s achieved everything that she’s achieved, both before she played field hockey and ice hockey at Princeton and since she graduated in 2000 and embarked on a path that has led her to her newest, well, what would you call it?

It’s a business venture, but that doesn’t really describe what she’s doing. No, the one word that best describes the path she’s going down now is this: “Passion.” Gia Fruscione’s passion is “Let Her Play,” and it’s those three words that have gotten her to, somewhat ironically, sit still for 30 minutes.

“Let Her Play” is the name of the company that grew out of a conversation she had with a professor at the University of Denver, where she was working on an MBA, this after she earned a doctorate in physical therapy from Northwestern.

“We were writing a reflection paper, a career reflection piece,” she says. “I wrote about what is now ‘Let Her Play.’ I told the professor, ‘when I have my millions,’ and he said ‘you can do this now; you don’t need to have millions.’”

And from that, “Let Her Play” has become a reality. Fruscione’s passion, er, non-profit, is focused on getting as many girls involved in as many sports in as many communities as possible. She has worked with local recreation departments and leagues to introduce her program, and she has also partnered with college women’s teams, to give young female athletes role models in their lives.

Princeton was, of course, a natural partner for her. “Let Her Play” had its first on-campus event two weeks ago, at the Princeton-Lafayette field hockey game on Bedford Field. The program comes to the new Myslik Field at Roberts Stadium Saturday for the women’s soccer game against Dartmouth.

“Sports build skills that are needed to be competitive in life,” she says, “and that includes sports on the social level, not just the competitive level.”

Her eyes were opened to the disparity of athletic participation between boys and girls by the stats that she read through Project Play at the Aspen Institute, near her home in Edwards, Colo., which is two hours west of Denver in the Vail area.

“Only one in three girls between six and 12 was playing a sport in the U.S., and that was before Covid,” she says. “Also, girls drop out of sports at a rate of 1.5 times that of boys by age 14. What that told me was that we’re not getting girls into sports, and we’re not keeping them in sports.”

Beyond the youth level, there are even more dynamic statistics.

“In 2017, I think, the NFL did a women’s summit in conjunction with the Super Bowl,” she says. “One of the stats that was presented said that 52 percent of women executives played a sport in college and 94 percent played a sport at one time. There was a seven percent wage gap between athletes and non-athletes. There are also a lot of intangible skills that came out of playing sports.”

As she speaks, she is sitting in the Princeton Stadium press box. From her seat in the front row, she can look out and see Jadwin Gym off to the left. It was there that the Fruscione connection to Princeton began.

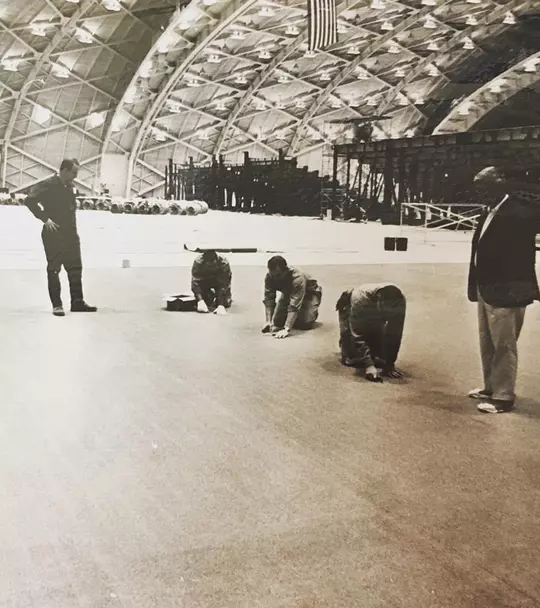

Her grandfather had immigrated from Italy and started a flooring business in Trenton. As part of that business, he laid the first basketball courts in the new Jadwin Gym, which opened in 1969. Fruscione grew up near the Princeton campus and was a field hockey All-American at Stuart Country Day School.

“I was a first generation college graduate,” she says. “When my grandfather found out I’d gotten into Princeton, to say he was elated is a big understatement. He passed away my sophomore year, and I put a Princeton hat into his coffin. I think a lot of what carried me into Princeton and let me do well here were skills I got from athletics.”

Her Princeton career was divided into two parts, pre-broken leg and post-broken leg. Her freshman fall was spectacular, as she earned Ivy League Rookie of the Year and first-team All-Ivy League honors as the field hockey goalie. Princeton entered the NCAA tournament that year, 1996, as the 17th-ranked team in the country and then made it all the way to the final, upsetting highly favored Old Dominion in the semifinals. When it was over, Fruscione was on the NCAA all-tournament team.

“That was a crazy run,” she says. “I know it’s a cliché, but what I remember most is the team aspect. Being together on the buses. There was a community aspect. What stands out is the time we spent together as a team.”

As a sophomore in 1997, she was once against first-team All-Ivy League. She also played ice hockey her final three years after missing her freshman year to play for the U.S. national team in field hockey in Chile that winter. Then, two days before the start of her junior field hockey season, it all changed.

“I went out for a slide tackle and got stuck in the turf,” she says. “My foot stayed. My leg went. That was it.”

She had surgery the next day and was on the sideline for the opener the day after, but she never played field hockey again. She did come back for her last two years of ice hockey, but her field hockey career, both Princeton and international, was over.

“There’s a resiliency that goes along with being hurt,” she says. “You have to figure out how to make lemonade out of lemons. There’s a lot of personal growth and learning that comes out of being hurt. There’s the physical part. There’s the emotional part. I went from being the starting goalie to being unable to play, just like that.”

It was her injury that at least somewhat pushed her into physical therapy, in which she got her Ph.D. at Northwestern. She then spent 14 years in clinical practice, an experience that led her to conclude that the trend in youth sports towards specialization at early ages was having profound effects on the athletes, and most of them were not positive.

“Specialization is linked to potential health issues,” she says. “There are definite neuro-developmental benefits to not specializing in one sport. You ask a child who’s 8 or 9 or 10 to commit to a sport five days a week, for thousands of dollars. And if they don’t want that, what options do they have? What about the kid who loves basketball but can’t make the middle school team. We’re giving them a place to play.”

Fruscione saw first-hand what the youth sports culture is all about with the experiences of her own children, who are now 10 (Gabi) and six (Alexandra). Her husband is Craig Loizides, who played tennis at Princeton and graduated in 1997.

And so it was that she took her experiences in physical therapy, in business school, in working with start-ups and with coaching her children, and started creating a business model. Out of that “Let Her Play” was born.

She started with her 10 C’s, the core values and soft skills that come from competing in sports: character, communication, competition, community, courage, commitment, centeredness, collaboration, contribution and confidence.

Now she had a vision and a mission statement. Her goals were clear. Next she had to figure out how to get it off the ground.

“Those 10 values are great,” she says, “but I also needed the value of the sport to come through to the girls. I started working with local rec departments. I learned from working with startups that you have to put yourself in the customers’ shoes. A lot of the people who coach the girls are fathers. There are way more men who coach girls than women. They’re coming from work. They don’t have much bandwidth for additional learning.

That’s where the idea for partnering with college teams came to her.

“I felt it was really important for girls to get a woman’s perspective on what playing sports means to them,” she says. “Who better to do that than women college athletes? What we ask them to do is record a video on their phone that’s maybe 30 seconds to a minute long. Then the coach can play it for the girls he’s coaching. All he has to do is turn his phone around.”

To make it even more real for the girls, “Let Her Play” takes them to the college games and gives them a chance to meet the players.

“My older daughter started playing hockey a few years ago,” she says. “It was with the girls’ rec program. Intro to hockey. It was the rec director and a bunch of dads. I went out onto the ice, and I can’t tell you how many girls came up to me and said ‘wait, you actually played hockey. Really?’ They need to connect the dots in ways that they haven’t been. They have to understand where it can take them.”

Like any new business, Fruscione’s needs capital to get going. She has gotten some buy-in from donors and sponsors who believe in what she’s doing, and she also applies for grants. The rec departments who have bought in already, and there are about 20 so far, pay for the service, and those funds help offset operating expenses. She also has gone into disadvantaged areas and used “Let Her Play” money to help pay for opportunities that otherwise wouldn’t exist.

“I was just out in Phoenix at a rec department conference,” she says. “I gave out 75 business cards. We’re going to try to expand this on a regional level with an anchor college in each region. What we’re doing here that’s a bit unique is that we’re working with athletes to bring kids to games on campus. You see them in the video, and then you see them play on campus and get to meet them. It’s a great mentorship opportunity for the athletes.”

Her hope is to have enough growth to hire some additional staff. In the meantime, she’s a one-woman whirlwind, distributing orange “Let Her Play” t-shirts, setting up the table at events, organizing, promoting, talking, getting the word out.

It hasn’t left her much time to sit still, but that’s okay. It’s not her style. And she has a passion to make into reality.

— by Jerry Price