Princeton University Athletics

Book Excerpt - The First 50 Years Of Women's Athletics: Wendy Zaharko

January 20, 2021 | Women's Squash

When Wendy Zaharko was seven years old, there was a group of teenage boys who used to play basketball in the house across the street.

“I was fascinated by their athleticism and loved watching them,” she says. “When the ball would go over the fence into the next yard I would run and retrieve the ball and throw it back to them. I felt really important.”

The boys were about 10 years older than she was. She remembers them vividly, especially one of them in particular. The mother of her best friend, who lived next door, would often say that someday that boy was going to grow up and make something of himself.

Zaharko saw him again in Colorado a few years back, when he was skiing in her adopted home state. She went up to a few of the people who were with him and asked them to tell him that she was there, and so they did.

Those “people” were actually Secret Service agents. The teenage boy was Joe Biden.

“He turned around and saw me there and yelled out ‘Wendyyyyyyy,” she says. “He told them to let me come over and chat with him.”

She’s also had another brush with a vastly different kind of famous person. This came when she was doing her residency in internal medicine in Philadelphia, in 1985. The MOVE anarchists had been in a stalemate with the Philadelphia police, until a bomb was dropped on their West Philadelphia rowhouse, starting an inferno that resulted in 10 deaths and 65 destroyed houses.

One of the leaders of the movement was a woman named Romona Africa. She was brought into the ER, where Zaharko was on the trauma team that day.

“It was so intense,” Zaharko says. “There were police everywhere, and they had their long guns pointing upwards. For us it was like running a gauntlet. Romona came in cursing at me. I told her that by the time she left we were going to like each other. There was some strong humanity that flowed between us. We were just two people trying to work through a very difficult situation. A few hours later she smiled at me and said, ‘I like you white girl.’ The feeling was mutual.”

When it comes to big names, there have been few bigger in the first 50 years of women’s athletics at Princeton than that of Wendy Zaharko. Some of her contemporaries refer to her solely as “Z,” and there’s an awe in all of their voices when they talk about her and what she did in the earliest days of Princeton women’s squash.

Or, more accurately, what she didn’t do in those earliest days. Lose.

Wendy Zaharko was the first Princeton woman to win a national championship, something she did in the winter of 1972, as a Tiger freshman. She would win the collegiate national championship again as a junior and as a senior; as a sophomore, she missed the NCAA championships because of a conflict with coach Betty Constable over Zaharko’s participation in the U.S. national championships.

In her entire time at Princeton, she never lost a match, or for that matter, even a game.

She grew up north of Wilmington, Del., and she first had a racket in her hand when she was five. It was a badminton racket.

“My father was one of the top badminton players in the world,” she says. “He was Canadian. It was a big sport there and in my town of Wilmington. He got me started with badminton. Then tennis.”

She would attend Mount Pleasant High School, where she played field hockey while also throwing the javelin for a club program. She also started playing squash in 10th grade along with her dad.

“My father and I had so much fun learning that game. Especially the angles. We’d laugh so hard as we tried to figure out the geometry of the game. The badminton and tennis combination helped me a lot. The wrist. The ground strokes.”

She started playing on public squash courts, and a former international champion named Dan Martella saw her hitting one day by herself.

“He offered to show me a few things,” she says. “The first shot he showed me was the ‘put the ball through the front wall shot’ and the second was the ‘I don’t care shot.’ Those two shots sure appealed to me, and that was the beginning of my love affair with squash.”

Zaharko started to play in some local tournaments. She also started to get involved in something else.

“The first shot he showed me was the ‘put the ball through the front wall shot’ and the second was the ‘I don’t care shot.’ Those two shots sure appealed to me, and that was the beginning of my love affair with squash.”Wendy Zaharko

“I was very committed to the anti-war movement – demonstrations, marching on Washington, leaflets and petitions,” she says. “I was going to go to Swarthmore, because there was a big anti-war effort there. While playing in a tournament at Pretty Brook Club in Princeton, I met a man from the Class of 1961 named Jay Webster. He asked me where I was going to go to college, and I said ‘Swarthmore.’ He asked me why not Princeton, and I told him that Princeton didn’t take girls. A few days later, an application showed up at my house. It said ‘fill this out and send it back ASAP’ and was signed ‘Jay Webster ’61.’ That fortuitous encounter changed the course of my life.”

She and Jay have maintained a close friendship for more than 50 years, and they often ski together since he moved to Colorado in 1986.

“They were great times on the campus back when coeducation was getting going,” she says. “Princeton did a great job for the women just by listening to us. I think they were well-prepared for most things. Some of the facilities, however, definitely needed improvement. The locker rooms were awful. But the squash courts, the tennis courts, they were unbelievable. It was an interesting time, and I think we women did a great job of negotiating with the male teams and coaches about where we could play, when we could play, where we would dress and shower and where we would get treatment for our injuries. The healing of wounds were the sole property of the male locker rooms back then, so when one of us coeds had an injury, we’d head to Caldwell Fieldhouse and the trainer would give a heads up to the male athletes shouting ‘Female athlete onboard; clear out men,’ as lots of toweled men with hairy legs would go dashing by to take cover.”

Zaharko’s squash career at Princeton almost ended before it began. She had hurt her back playing field hockey and throwing the javelin several years earlier, leaving her with a spine that would slip in and out of alignment (spondylolisthesis, literally “slipping spine”). When it was “in,” she was pain free and able to compete. When it was “out,” so was she, as in complete immobility.

It was during the fall of her freshman year, in 1971, when she slipped on some sweat on a Jadwin court. By the time she walked across the campus that night for dinner, she knew something serious was wrong.

This time, she needed surgery to fix the problem. The surgeon told her she’d be able to walk again, but he couldn’t guarantee she’d ever return to playing squash. She spent most of her freshman spring semester in a neck-to-knee body cast flat on her back in bed.

“I felt like a turtle in a shell and I looked like one too,” she says. “It was crazy to be encased in this gigantic cast.”

When she was finally sawed out of the plaster, the first thing she had to do was be taught how to walk again. Returning to Princeton that fall for the second semester of her freshman year, she miraculously had healed enough to return to the squash courts, and on Feb. 29, 1972, she defeated her teammate Sally Fields 15-4, 15-2, 15-10 to win the national championship.

“She’s just in a class by herself,” Constable said at the time. Her relationship with Constable was not always great, especially during her sophomore year.

She would not get a chance to win her second title the next year, as Constable made her choose between a regular-season match against Vassar (beaten by the team earlier that year by 9-0) and the U.S. championships. She chose the national event instead.

“She told me it was either Princeton or Wendy Zaharko,” she says. “She did what she thought she had to do. I did what I thought I had to do. I would have loved to win four collegiate championships, I felt I had to stick to what I thought was important.”

Zaharko did have one loss that sophomore year at Princeton. It came not in squash but in ping pong, when she lost to Director of Athletics Royce Flippen in an exhibition match after the men’s University championship match. The Daily Princetonian referred to an “overflow crowd at the Pub” that watched the matches.

She came back to the team the next year and cruised through two more seasons, winning two more titles. Along the way, she became close with several other early women athletes.

“Cathy [Corcione, the Olympic swimmer and fellow collegiate national champion] and I were next door neighbors,” Zaharko says. “She was remarkable and could have been a stand-up comedian. All the women athletes knew each other. We were jocks. We’d play stickball, throw the football, and play frisbee. I had a roommate who was a Phi Beta Kappa. She would say ‘you’re always in the paper and everyone knows you. I don’t get any points for knowing about Shakespeare and Dickens.’ And she was absolutely right, but back then we women jocks were getting a lot of print and none of us seemed to mind.”

Her surgical experience did more than just get her back on the squash court. She’d come to Princeton interested in “boys, squash and international relations,” but she detoured from that course of study into an interest in medicine.

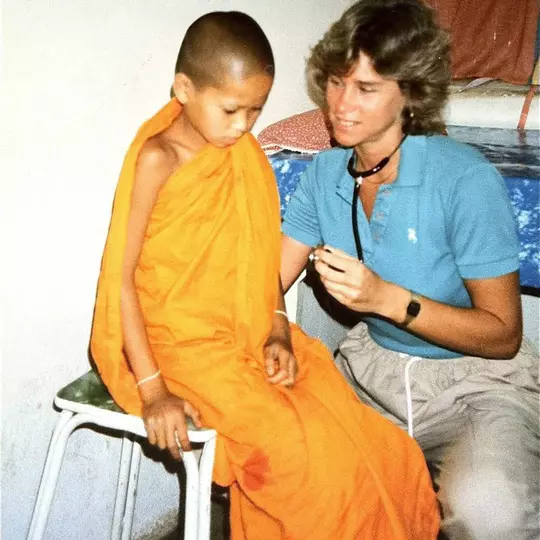

She’d start medical school at Jefferson and finish at St. George’s, Granada, where she had, in her words, “an incredible experience.” She also spent a semester in England doing clinicals, making house calls in the countryside and studying tropical medicine in London.

“It was so interesting to see a public health system that worked so well for so many,” she says. “There was an art to their medicine which I’ve always found lacking in American medicine. The English taught me the art of listening to patients, which is what really counts when you’re trying to heal people.”

Travel also became a passion for her, and that happened through squash. During college she traveled as a member of a North American team to Australia and New Zealand. Later she would play with the American team in the Queen’s Jubilee matches in London.

“I got the travel bug from these competitions,” she says. “I ended up traveling all over the world on a shoestring budget with a backpack and always strapped to it was a squash racquet and tennis racquet.”

Eventually she’d make her way back to the Princeton area, where she’d work in emergency medicine and urgent care and raise her two children.

In 2003, after her father passed away, she decided to take a year and move to Colorado, so she rented her house in Princeton and headed west, partly to ski and partly to give her son and daughter a different perspective. They flourished in the mountains and the incredible outdoor lifestyle it offered. Zaharko still lives in Colorado and returns to Princeton often.

Since 2009, she’s dedicated her professional career to cannabis medicine, working with patients who have a wide range of issues, such as Parkinson’s, Multiple Sclerosis, cancer and severe pain, as well as mental health conditions such as bi-polar and PTSD. She is currently finishing a book about her cannabis practice with her former roommate Pamela Candusso Hirsch.

In 2011, Zaharko met up with Peter Lewis ‘55 since they both lived in Aspen, and they worked together on the legalization of both medical and social cannabis.

“We both knew that the way to legalize cannabis was through medical. Show the people that it was a safe and effective medicine. Peter was very strategic and he used me as his eyes and ears on the front lines of medical to help determine where his backing would be most helpful for social legalization. For me, it was so much fun to work with someone who loved Princeton as much as I did. Peter had also been a fan and player of squash.”

It’s been nearly 50 years since she was one of Princeton’s most dominant early athletes. It’s been more than 50 years since she chased down the basketball for Joe Biden.

She also was able to reconnect and reconcile with her college coach, who was one of the towering figures in the early days of women’s athletics.

“Coach Constable and I became quite good friends,” Zaharko says. “When I moved back to Princeton with my family, Betty and I would sit together at matches and critique the players. When I was asked to read her citation for the College Squash Hall of Fame in Philadelphia, I happily did so, followed by a big hug. She also invited me as one of her two guests to her induction into the National Squash Hall of Fame. Also, when Betty went into the Princeton Hospital, I visited her numerous times. She was always a hoot to be around, and even as she slowed down there was never a dull moment.”

Zaharko was part of a generation at Princeton that needed to make its own way and, more than that, needed to make a statement on the value of women’s athletics.

“The women athletes were the ones who really brought the alums around to accept women at Princeton,” she says. “We were good ambassadors. I used to get letters from old alums, crazy letters. I got one from Michigan that was 25 typed pages. There’s no doubt that co-education changed and helped Princeton. When you add 50 percent of humanity to a great institution of higher learning it can only make it an even better ‘best darn place of all.’ I was there to get an education, and there’s a lot of education to be gotten from sports.”

.png&width=24&type=webp)