Princeton University Athletics

Feature Story: Bill Carmody And His Guys

February 01, 2023 | Men's Basketball

Princeton-Cornell men's basketball tickets

Yes, the man leaning against the railing is smiling. No, he’s not fooling anyone.

The railing that Bill Carmody leans against is backed up by the beach and then the Atlantic Ocean. He’s 71 years old now, living two blocks from here. In fact, his address today is the same one he had when he grew up here as one of 11 siblings. He’s on the boardwalk to get his picture taken.

To his right, looking north, the outline of Asbury Park is barely visible through the gray. It’s quiet at this time of year at the Jersey Shore; the only people in view are an older couple who walk in black parkas hand-in-hand down the beach and a jogger who runs past and continues on her way up the boardwalk, towards Belmar and Avon by the Sea.

“Are we done?” Carmody asks.

No, he’s told. The old couple is still in the background. And so he keeps smiling.

“You know I hate this, right?” he says.

It’s damp and chilly, and the wind is blowing off the ocean just enough to make it feel more wintry than it really is. At the same time, it’s remarkably peaceful, almost eerily so if you contrast it with what it will be like on this same spot in July and August. In fact, the only sound right now is coming from the waves that smack against the jetty about 50 yards away.

In this moment, it’s hard not to think back 27 years earlier, to that day in Indianapolis, when he was seated at a small, circular table. It was his introductory press conference as Princeton’s new head men’s basketball coach, or at least what passed for his introductory press conference. It was in the cavernous media room at the old RCA Dome, where two days later Princeton would defeat UCLA 43-41 in the opening round of the NCAA tournament.

It was also three days after Princeton defeated Penn 63-56 in overtime in a one-game Ivy League playoff to get the automatic NCAA bid. Pete Carril, who had been Princeton’s head coach for 29 years and for whom Carmody had worked for 14, announced afterwards that he was stepping down and that Carmody would be his successor, something even Carmody himself didn’t know at the time.

Sitting at that small table in Indianapolis, Carmody was the center of attention. He smiled. He said all the right things. In fact, he was a natural at it. If you knew him, though, you knew he wasn’t fooling you then either.

“He hates the spotlight,” says Princeton head coach Mitch Henderson, who played for Carmody and then was Carmody’s longtime assistant at Northwestern.

“At his core, he’s an introvert,” says Gary Walters.

The former Princeton Director of Athletics and Carmody go back to Carmody’s days at St. Rose High School in Belmar, and Walters coached him at Union College for Carmody’s first two seasons there in the early 1970s. As Princeton’s AD, Walters also hired him, officially so, as Carril’s successor.

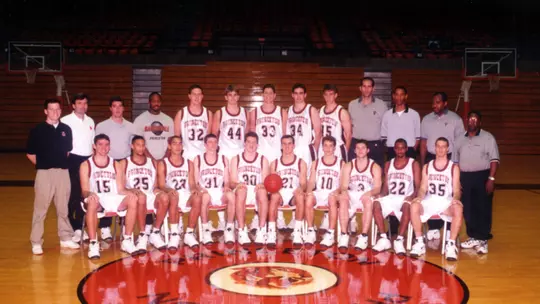

It's been 25 years since the Princeton men’s basketball teams of 1996, 1997 and 1998 completed one of the greatest three-year runs in Ivy League history and stamped that time as one of the iconic moments in the entire history of Princeton athletics. The names from that era are familiar and legendary: Steve Goodrich, Gabe Lewullis, Sydney Johnson, Chris Doyal, James Mastaglio, Brian Earl and of course Henderson. They were led by inarguably the greatest coaching staff the Ivy League has ever seen, with Carril (who passed away this past August at the age of 92), Carmody, Joe Scott, John Thompson III and Howard Levy.

Those teams will be honored before the game Friday night at Jadwin Gym, as Princeton plays Cornell, whose head coach is Earl. Most of the players and coaches from that era will be in the building.

So, too, will Carmody. He’ll be there for one reason, and it’s not to bask in any glory. No. He’ll be there for his players, though he never refers to them that way. Nor does he call them “athletes” or “men” or “teammates” or anything else. To Carmody, they’re always “the guys,” and it’s for “the guys” — his guys — that he will be back.

The era that is being celebrated grew its roots well before the wins over Penn and UCLA. The man who was at the center of all of it was Carmody, who first helped put together and develop the guys who finally caught the arch-rival Quakers and then, after he took over as head coach, led them to amazing heights.

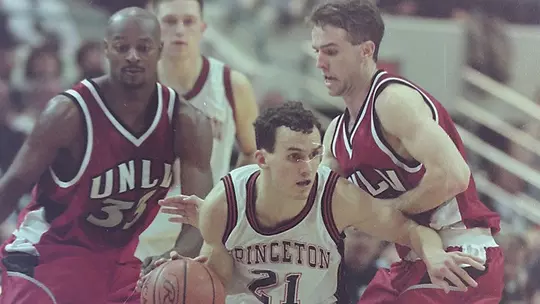

Carmody would be Princeton's head coach for four seasons, the first two of which saw his teams go 51-6 overall and 28-0 in the Ivy League. His 1997-98 team went 27-2 and defeated UNLV in the opening round of the NCAA tournament after a regular season that ended with a top 10 national ranking. Even when the NCAA streak ended, Carmody led Princeton to two NIT appearances, including two wins and a quarterfinal appearance in 1999, not to mention the epic 50-49 comeback win at Penn in 1999 after the Tigers had trailed by 27 with 15 minutes to play.

He’d leave Princeton for Northwestern in 2000, where he’d stay for 13 seasons, leading the Wildcats into the Top 25 for the first time in 40 years. He’d then coach at Holy Cross for four seasons, including an NCAA tournament appearance in 2016, before retiring after the 2019 season.

“He has by far the best basketball mind I’ve ever been around,” says Thompson, who played for Carril, is the son of a Hall-of-Fame coach and who coached Georgetown to the Final Four. “He gets the most out of each person. He knows their strengths, and he also knows how to make them fit into a team concept to make the team better. He’s brilliant at it.”

“He has this amazing ability to watch a small amount of film and get to the essence of a team quickly,” says Levy, now the head coach at Mercer County Community College. “It was amazing. He’d watch film, write some stuff down, and in 15 minutes he knew exactly how to beat them, knew what they did, knew what each guy’s strengths and weaknesses were.”

Carmody is defined best by a unique dichotomy: He is at once extremely intense and extremely laid-back, if such a combination is possible.

“That’s him,” Thompson says. “That’s a pretty good way to describe him.”

His laid-back side makes him, to use Thompson’s words, “completely genuine.” Carmody is that, for sure. He’s funny, in a subtle, understated way. He’s warm. He has a way of connecting with people that draws them in immediately. He has interests that go way beyond just basketball.

“He’s Bill,” Henderson says. “You want to be around him. I cherish the moments I’ve spent with him. He’s incredibly close to the people he’s close to, if that makes sense. His family. His childhood friends. When you’re around him, you always feel good. And for someone who doesn’t like the spotlight, he can turn it on and be a one-man act. He can be hilarious.”

The intense side makes him one of the most competitive people you’ll ever meet. Maybe the only thing he hates more than the spotlight is losing. Anyone who has ever run into one of his elbows during a pickup basketball game can tell you that.

“Playing Penn at the Palestra or lunchball?” Thompson says laughing. “It doesn’t matter to him. He’s playing to win.”

Maybe that’s an offshoot of being from such a large family. He moved to the Shore from Cranford when he was five and there were already eight children on board. His father, who worked in construction for a large company before he passed away from cancer when he was 49 and Carmody was a high school sophomore, bought the house where Carmody now lives all these years later. Back then, as the fifth of 11 children, he shared a bedroom with three brothers, on two bunkbeds.

“You could get big houses for not a lot of money at that time,” Carmody says. “Our house didn’t have heat, so he had to put the heat in. It was a great place to grow up. It’s a great town. There were kids everywhere. We were always in the street playing stickball, touch football. We were outside all the time. Now most of the houses are closed up for the winter. On my street, only three houses have someone here all year round. Back then, there were always kids around. There aren’t many anymore.”

Carmody grew up playing baseball and basketball in the local leagues. He first came onto Walters’ radar when Walters was still coaching at Middlebury, but they would team up together on Walters’ first Union team instead.

“He was a very heady, very savvy point guard,” Walters says. “He could do a little bit of everything. He might have been a step slow for Division I, but he was really good. And he was competitive. Very, very competitive.”

After graduation in 1975, Carmody starting his coaching career at Fulton-Montgomery Community College outside Albany before being an assistant at Union under Bill Scanlon, his coach his final two years as a player after Walters had left for Providence. He was set to join Walters’ staff in Providence but that fell through when Walters left coaching, so Carmody returned to Spring Lake and working in construction — “We did foundations, masonry, heavy cement work.”

His professional path changed dramatically when Eddie Reilly left Carril’s Princeton staff to go back to Holy Cross as an assistant. Walters, who had played for Carril at Reading High School in the early 1960s and then coached with him on the 1975 NIT championship team at Princeton, recommended Carmody to Carril to fill the spot.

“Pete called, and he asked me to come see him that Monday,” Carmody says. “He said ‘just don’t wear a tie.’ He basically offered me the job right there.”

Carmody started in 1982. One of the first players he’d recruit would be Scott, another Jersey Shore guy.

“He was such a big help during my four years,” Scott says. “He was there every step of the way to helping me become a better player. He’d always say something small that would help you. He’d say ‘try this, or did you ever think of doing that?’ He came up to me before we played Delaware my senior year and just said 'make us win the game.’ He was always there to really help you, and I’m not the only guy who felt that way.”

Carmody helped build and coach the 1989-92 Tiger dynasty, which won four straight Ivy League titles and then lost four NCAA first-round games by a combined 15 points, including the legendary 50-49 loss to Georgetown in the 1989 tournament. Penn, led by future NBA players Jerome Allen, Matt Maloney and Ira Bowman, would then go 42-0 in the league the next three years, but only Bowman would be left from that group for the 1995-96 season.

Princeton, meanwhile, had begun to put together the pieces for the teams that would make history.

“I saw Mitch at Five-Star,” Carmody says of the famous basketball camp. “My scouting report on him was that he was crazy but fast as a son of a gun and we needed that guy.”

Of course, Carmody didn’t really say “son of a gun.” You can use your imagination there.

“He said that about me?” Henderson says. “I like that.”

“Sydney was at Fork Union for a PG year and I heard he was really good,” Carmody says. “I saw him and loved him, but it was too late because the admission deadline had passed. Then I found out he’d applied on his own and gotten in. Doyal was terrific. I could say a lot about that guy. He could really pass. We worked hard on Mastaglio. He was another guy who was underrated. Gabe was great. Everyone wanted Stevie [Goodrich]. Same with Brian. We worked hard to get them.”

The 1994-95 Tigers started no seniors, though it brought Rick Hielscher, who would earn his second first-team All-Ivy honor, off the bench. The team went 16-10 that year, including 10-4 in the Ivy League, and the season ended at Jadwin with a 69-57 loss to the Quakers. Before the start of the next season, there were already major changes brewing.

“During that summer, Coach [Carril] and I had some long talks,” Walters says. “He said he was going to be stepping down after the next season and that he was serious this time. I worked with the University administration to waive its policy of conducting national searches so that Bill could be named the new head coach. At that point, he’d been there 13 years already. I’d coached him and known him a long time, and I knew he’d earned the right to succeed Coach.”

There was one caveat — nothing was going to be announced until the end of the season. The circle of people who knew of Carril’s impending retirement was very, very small. Even Carmody didn’t know that it was to be Carril’s last year, let alone that he was already set to become his replacement.

In the meantime, there was still the matter of catching Penn. The teams met in the first Ivy game of the year, and it was an excruciating 57-55 loss for Princeton at Jadwin.

“In some ways, those guys represent what the history of Princeton Basketball is all about,” says Scott, who is now the head coach at Air Force. “They were good players, and maybe there were people who didn’t think they were at that high a level. They just grew into being those kinds of players. More importantly, though, the emphasis was always on the team. Those guys brought out the best in who they were individually because the put the team format first. They each had their moment where the lightbulb went on. I remember we were up at Dartmouth and Stevie had been struggling a bit and then he just took that game over. It was late in the game, it was close, and three straight times we threw it into him in the post and he scored. He made this lefty hook and I said ‘woah, there it is.’ It all just started to gel. It was that kind of process. That’s when everyone started to think ‘hey, we have a pretty good team here.’”

Princeton would win its next 12 league games after that first loss, while Penn would stumble against Dartmouth and Yale, leaving the Tigers a game ahead of the Quakers heading to the Palestra for the final game of the regular season. A win would mean an outright Ivy title; a loss would mean co-champs and force a one-game playoff. The final was Penn 63, Princeton 49, and it wasn’t really that close. The win was Penn’s eighth-straight against Princeton, which meant that no player on the Princeton team had ever beaten the Quakers.

The playoff game was set for five nights later at Lehigh. While most of the focus in the years since has been on the UCLA game, pretty much to a man every player has said that the playoff game meant more to him. Regardless, the night of March 5, 1996, was unlike any other in Princeton men’s basketball history.

“It was hell after we lost to Penn,” Carmody says. “We had just lost to them twice, once five days earlier, and now we had to play them again. I remember the shootaround at Lehigh that day. Pete used to treat them like practices. It was pretty intense. I wouldn’t say it was a good practice, but it was a very intense practice.”

Lehigh’s Stabler Arena was jammed, split right down the middle between orange and black and red and blue. Unlike the previous eight meetings, Princeton took control early and played from ahead, building a lead of nine at the half and then stretching it to 13 with nine minutes left. Celebration time, right? Nope.

Penn came all the way back, first by getting to the foul line with regularity and then, after a defensive breakdown in the final seconds, tying it on a wide-open Bowman three. The score might have been 49-49 heading into overtime, but all of the momentum favored Penn. Princeton regrouped, though, and Johnson made the biggest shot of the night, a corner three as the shot clock expired with just over a minute left to snap a 54-54 tie. Princeton would win 63-56.

The story of the night, any other night, would have been Lewullis. Inserted into the starting lineup, the freshman responded with a team-best 15 points in 44 minutes, and his defense on Penn’s Donald Moxley was even more important. Moxley had torched the Tigers for 35 points in the two regular-season games, but Lewullis hounded him into an 0 for 14 night in the playoff.

Throw in the fact that Lewullis was local, having graduated a year earlier from Allentown Central Catholic High, and he was the story. Until, that is, Princeton entered its lockerroom. That’s where Carril stood, next to a chalkboard that said “I’m retiring. I’m very happy.”

Oh, and it also said that Carmody would be the new coach. Carril repeated that at the postgame interview, where he had just dropped his bombshell news.

“I didn’t know anything about it,” Carmody says. “I had to immediately say ‘hey, let’s see what happens. There will be a search.'’”

Walters had worked hard to ensure that there wouldn’t be one.

“I had to go back to the administration and apologize,” Walters says. “I said I had no idea Coach was going to do that. I had to explain that he could be a bit of a loose cannon.”

By Tuesday in Indianapolis, everything was official, and Carmody had his introduction to the media. Princeton would famously win the game on the Lewullis backdoor layup, and then Carril’s Princeton career would come to a close with the loss to Mississippi State in Round 2.

Now it was Carmody’s team. Like it or not, he was the one facing the microphones and cameras. One of those asking the questions was Mark Eckel, then with the Trenton Times. Eckel has covered most major sporting events, including more than 20 Super Bowls and the NHL and NBA Finals, not to mention countless college and high school sporting events.

“I love Bill,” Eckel says. “He was great to cover as a writer. For all the coaches I’ve covered in all those sports, he’s right up there with any of them. You take over for Pete Carril, it’s not easy in a lot of ways. How many coaches take over for the legend and fail? He was taking over for Pete, and he obviously did well as a coach, but when you take over for Pete, he was legendary from a media standpoint as well. Pete had some of the greatest quotes of all time, but Bill held his own there too.”

“When I got the job, Harvey [Yavener, longtime local sportswriter] said to me ‘you ain’t gonna sleep anymore,’” Carmody says. “I said ‘I don’t think so.' I knew our guys and how they were. We had a great staff. We were in good hands with them.”

After Princeton almost defeated Georgetown in 1989, the following season began with the Tigers as something of a national curiosity. Everyone wanted to see the team that had almost taken down the Hoyas and marvel at the way they played.

The 1996-97 season was a bit different. Yes, there was interest in the Tigers after the UCLA win, but this was a different team.

“The next fall, the ball was just flying around,” Henderson says. “I remember that Bill said something to us in the fall of 1996 that was basically ‘throw it. Take chances.’ We all knew how to see the game. He just uncorked something in us.”

“I remember being impressed being in the room and talking basketball with Bill, Joe and John,” says Levy, who joined the staff for Carmody’s first year. “I thought that this was high-level stuff, and I hoped I could contribute something. They guys were so well-schooled from Coach Carril, and Bill thought allowing them to do more was perfect for them. I think with Coach Carril, if you were going to throw a backdoor pass, it had to be perfect. Catch it. Layup. Bill said ‘maybe throw it later. See what happens.’ The guys felt they had a little freedom, and it helped their confidence. To have that as your first real coaching experience, I thought ‘this coaching stuff is all right.’”

In typical Carmody fashion, he found the perfect way to describe it.

“It was like we were down at the park,” Carmody says. “I didn’t care who was called a forward or a guard or anything. I just wanted to put five guys out there who would play together. Pete put a lot of the stuff in, and they just kept getting better and better at it.”

Carmody lost his first game as head coach 59-49 at Indiana, but his Tigers ended up going 24-3 in the regular season (with wins over teams like Marquette, Texas A&M, UTEP, Rice and Rutgers) and sailing through the Ivy season unbeaten at 14-0. Princeton fell 55-52 to California, led by future Hall of Fame tight end Tony Gonzalez, to end his first season.

Maybe more telling than anything about Carmody, though, was something that happened in December of 1996, with the sudden passing of Henderson’s father.

“Bill came to my room when my dad passed away,” Henderson says. “He’s the one who told me. He’s the one who drove me to the airport that day. My father and Bill. Those are the two people who’ve impacted me the most.”

“He really, really cares about people,” Levy says. “When you’re with him, he’s completely engaged in a way that not many people are.”

His second Princeton team managed to be even better than his first. The season started with wins over Texas and North Carolina State to win the Coaches vs. Cancer Classic at the Meadowlands, and the winning just kept going from there. Princeton took down Wake Forest, also at the Meadowlands, this time in the Jimmy V. Classic, and then swept Drexel and Niagara at Madison Square Garden to win the ECAC Holiday Festival title.

Princeton’s only regular season loss would be by a 50-42 count at No. 2 North Carolina, who was playing a night game after the No.1 team in the country, Duke, had lost earlier in the day. The game was tied at the under-four media timeout.

The Tigers moved into the national Top 25 early in the season and continued a steady rise to No. 8 by the end of its second-straight 14-0 Ivy run. Princeton was a No. 5 seed in the NCAA tournament, where it took down UNLV 69-57 in the first round. It ended two days later against Michigan State 63-56, after the game had been tied with just over a minute to go. With four of the same starters, Michigan State would win the NCAA title two years later.

“We had a 27-2 season,” Thompson says. “By any measure we had a hard schedule, and we went 27-2. As good as those guys were, they all played for each other. They played as hard as they could for the betterment of the team, and that was all Bill.”

As hard as it is to believe, that season was 25 years ago. It’s also amazing to consider that from that era, Carril, Carmody, Scott, Thompson, Levy, Johnson, Earl and Henderson would all become college head coaches, which is a statement on the competitive nature of the program.

“Bill is a basketball guy through and through,” Henderson says. “I remember when I was just starting out, I was going to do a clinic in front of some high school coaches. I was really nervous. I took some notes into his office, and he said ‘it’s just basketball; just be yourself.’ He had such a great way of simplifying things. He may not even realize it, but that’s such a gift. I think I can see the game quickly, and a lot of that is from playing for Bill and working with him. It’s the way he sees things in general. He’s always listening, always watching intently. He picks up on everything you say and do. He may not say it, but he definitely sees everything.”

He could have a basketball job tomorrow if he wanted, either in coaching or television. He’s not there now, though.

In many ways, he’s the same Bill Carmody he’s always been. He uses the same hand gestures when he speaks, the ones that punctuate his statements perfectly. His humor is still hilariously subtle and lightning quick. He has the same warmth he’s always exuded, the one that has allowed him to build such deep and lasting connections.

There is, though, something about him that’s impossible to miss if you’ve known him for a long time. It’s not a lack of energy. It’s not that his competitive fire has burned out.

It’s a sadness. An unmistakable sadness.

While at Union, Carmody met a woman on the women’s basketball team, and they would build their lives together. Barbara, “Barb” as most called her, was the perfect match for him. A woman of grace and charm, she was his partner in every sense.

When Carril called to offer Carmody the assistant’s job at Princeton, he was with Barb, “eating pasta in Barrington, Rhode Island.” She was a constant presence at Princeton games during his tenure, always with a smile and a hug.

Barbara Carmody passed away from pancreatic cancer nearly three years ago. She was 66 at the time of her death.

“I know this is a cliché,” Thompson says, “but more than any two people I’ve ever met, they were one.”

“She was such a great woman,” Walters says.

“She was a bright, shining light,” Henderson says. “Everybody loved her. They were really, really close. It was crushing when she passed away.”

Levy and Scott basically said the same thing, almost word for word.

“Obviously, husbands will always say they love their wives,” Levy says. “They were clearly each other’s best friends. They were really one unit. Bill and Barb. They were both great to be around. Whip smart. Compassionate. I think Barb, life-wise, she saw the whole floor. She saw everything. What they had was so special.”

“All husbands and wives love each other,” Scott says. “They also really liked each other. They enjoyed being together so much. It’s unbelievably sad.”

Bill and Barb had two sons, Michael and Edward, who are both grown and living a few hours from the Shore, Michael in Washington, D.C., and Edward in Boston. These days, Carmody spends his time reading, walking and listening to music. A lover of art, he’d like to spend some time in Italy.

Walking around his house, what used to be an unimaginably loud place with 13 residents is now quiet. There are pictures everywhere, and framed prints of famous paintings. He recently found some in a box that Barb had put in the basement at some point. Her presence in this house is still most clearly felt.

“She was special,” Carmody says of his wife, as he sees her handwriting on the box, whose top he removes to see the prints underneath. “We were together a long time.”

Just as Barb will always be a part of him, so too will he always be a part of Princeton Basketball history. He had the difficult task of following the legend, and he succeeded. Maybe he’s been a bit overshadowed by Carril all these years, but that doesn’t mask the fact that Bill Carmody has always been an extraordinary basketball coach.

“Ask anyone in the basketball world to name a coach they’d want to draw up the one play to get the one basket they need,” Levy says, “and they’d say Bill Carmody.”

He’ll be on the court to be honored before the game Friday night. And maybe being honored isn’t quite his element, but he’ll be surrounded by his guys, and that most definitely is. It’s something that, to a man, they all cherish.

Back along the railing on the boardwalk, the old people have finally moved out of view. A few seconds later, the pictures have been taken, the posing is over and the smile for the camera is replaced quickly by his real smile, the genuine one, the smile that is accompanied by his signature gesture of holding of his hands out, palms up, with his shoulders arched. It’s his way of saying “you know exactly what I’m thinking.”

His look is saying “you’re still one of my guys.”

In the January chill, you can’t help but feel warm knowing that.

— by Jerry Price

.png&width=24&type=webp)