Princeton University Athletics

So Long, Ty

March 12, 2010 | Men's Lacrosse

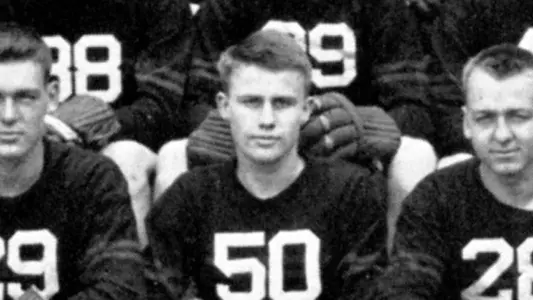

The picture is there, in black and white, looking out past the photographer with perfectly combed hair and the slightest hint of a smile, there on the bottom of page 65, right where he's been since the book was published more than 70 years ago.

It's the image that's in full color. It's the image of the boy on page 65 as he sat down to write the letter that is haunting.

"Dear Mac," he wrote to his younger brother, who was also in Europe, he in France, the brother in Italy.

And with that introduction, he is visible again.

Tired. Dirty. Unshaven. His eyes bloodshot; his uniform in disrepair.

The war all around him, and yet now a break, on this picture-perfect end-of-summer day, in this quaint little French countryside town. And now that he has a moment, he looks for a pencil, any scrap of paper, to put together a short letter to his brother one country over, an ambulance driver because he was too young to fight.

Can't you see him? Part war movie, part impressionist painting, the mind's eye is saying.

And with that, he begins to write.

He says a lot in his short note. Next to "Dear Mac" he has written "Somewhere in Southern France."

He talks about how proud he is of the French resistance. He predicts a Feb. 26 end to the war in Europe; he will be off by a little more than two months.

He talks about how much of the country he's seen, how beautiful it all is. He apologizes for not having proper stationery with which to write.

And then he's done, and so he says goodbye.

"So long," he writes. And then he signs it simply: "Ty."

Above where he has written "Somewhere in Southern France," he has written the date, in military style: "18 Sept. 1944."

Presumably he addressed an envelope and sent his letter away to the brother.

Three days later, Ty - Captain Tyler Campbell, Princeton Class of 1943, a member of the U.S. Lacrosse Hall of Fame - was killed, according to one report by German machine gun fire and according to another by a single bullet from a German sniper.

"It is with deep regret that I must verify the wire that you received concerning your son, Tyler," Major General John O'Daniel wrote to Campbell's parents. "You have my deepest sympathy in your bereavement. I can sympathize thoroughly as my only son, John W. Jr., was killed in action on September 20th, one day before your boy was."

At the time of his death, Tyler Campbell was 22.

"I'm 88 years old," says A. Samuel Cook, also of the Gilman Class of 1939 and the Princeton Class of 1943, "and I've never known a finer person than Ty Campbell."

Shortly after Campbell's death, a corporal named Burton Roberts wrote a letter to Campbell's mother.

"The men in his company were crazy about him," Roberts wrote. "They thought he was the best company commander in the Army. He was that and more. I never head him utter a harsh word to anyone. He led his men; he didn't have to drive them ... He did much for his country, and his characteristics, goodness, kindness, tolerance will live on in the actions of the men who were proud to call him their friend. When informed of your son's death, the Battalion Commander turned his back to everyone and for the rest of the day remained mute. There were many men who cried."

Wilbur McLean's grandfather crossed the Delaware River with George Washington, and Wilbur himself had the honor of essentially having the Civil War start in his front yard and end in his living room.

McLean owned a farm in Manassas, Va., and his farm included a stream called "Bull Run." The First Battle of Bull Run was fought on July 21, 1861, and it was the first major battle of the War Between the States.

By the time the day was over, nearly 5,000 men had died on Wilbur McLean's farm.

In an attempt to get away from the war, Wilbur packed up his family and bought a different farm, in Appomatox, Va. On April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered to General Grant at a table in Wilbur's house.

Wilbur's granddaughter married a man named Bruce Campbell, and they had four sons. The family ran a highly successful business that began as a sand, gravel and building products company and eventually evolved into commercial real estate outside of Baltimore called Nottingham Properties.

Tyler Campbell, the second of four brothers, was born on March 31, 1922. He was small, never weighing more than 150 pounds, but he was a great athlete and a great student.

He was named the top all-around student in his class at Gilman School, one of Baltimore's most prestigious prep schools. From there it was on to Princeton.

"We had about 40 boys in our class," Cook says. "And he was the outstanding young man of the class. I knew him his whole life. I grew up with him. Everybody loved him. He was a saint."

Campbell had played football, hockey and lacrosse at Gilman, and despite being small, he lettered in hockey, 150-pound football and, of course, lacrosse at Princeton.

After leading the 1940 freshman lacrosse team to an undefeated season, he was a first-team All-America in 1941 and 1942 as a goalie, though he would sometimes switch to a field position. Against Army in 1941 at West Point, he played goalie for most of the game before coming out and scoring what became the winning goal. At game's end, he received a standing ovation from the entire corps of Cadets.

The 1941 Princeton men's lacrosse team wasn't bad, finishing 7-3 that season, losing to the Mt. Washington Lacrosse Club, Maryland and Johns Hopkins. The following season, 1942, Princeton again lost to Mt. Washington, but the other seven games were all wins. The Tigers defeated Hopkins 4-2 as Campbell made 27 saves and Maryland 12-10, as well as Rutgers by a 17-0 score and Navy 12-1. At season's end, Princeton was voted the USILA national champion.

"He was an expert goalie," says Charles Kennedy, Class of 1942 and a lacrosse player. "I knew him to be a great player, a great athlete, a championship goalie."

Athletics was not his only gift. He was elected president of the freshman class and then re-elected after that. He served on several student boards, including the Student Honor Committee and the Faculty-Student Committee.

He was also top-notch student. His field was chemical engineering, and his plan was to graduate in three years and then join the Army. When he was unable to accomplish this, he made the difficult decision to leave school anyway.

"I debated a long time whether to leave Princeton or not," he wrote to Dean Christian Glauss in November 1942. "I feel that I was not wrong in my decision ... When this war is over, I am coming back to Princeton to complete my senior year. I imagine a lot of men "said" that during the last war, but I am really determined to get my B.S.E. degree from Princeton."

With that, Campbell gave up his final year of athletics and academics at Princeton and entered the military. At first he was going to become a regular infantry soldier in the mountain troops, but instead he was recommended for Officer's Candidate School at Fort Benning.

"He essentially had a staff job until they landed at Anzio," says Patrick Hughes, who married McLean (Mac) Campbell's daughter. "He asked to go to the line."

Before his death, Campbell would serve in North Africa and be part of amphibious landings in Sicily, Salerno, Anzio (where he was first wounded) and Southern France. He would be wounded twice, and he would earn a Silver Star, a Bronze Star Medal and an Oak Leaf Cluster to the Bronze Star Medal.

He was promoted to First Lieutenant and then to Captain.

On Jan. 31, 1944, he led his outnumbered platoon against a German unit that was firing on him and his men from a house. Campbell led his men to a covered position and then directed a mortar attack while standing in clear view of the house.

On May 28, 1944, he coordinated an artillery attack on another German position as shells exploded 10 yards from him, this after he again led his platoon into a ditch to shield them from the attack.

On Sept. 13, 1944, eight days before his death, he climbed a tree to give him a clear line of sight to the German position. Wounded once by a shot to his ear, he left briefly for medical attention and then returned to the same tree, ultimately spending 45 minutes in the tree until the German machine gun nest was wiped out.

"They put him in a hospital bed," Cook says. "He just got up, left the hospital and went back to the same tree. Unbelievable."

Five days later, he sat down to write his brother. Three days after that, he was dead.

"On the day that he was killed," General O'Daniel wrote to the Campbells, "near le Marchessant, France, he was leading his company up a heavily wooded hill and while personally directing a flanking movement of one of his platoons, was killed by machine gun fire. He died almost instantly on the litter his men were carrying to an aid station. He was buried on 23 September at the U.S. Military Cemetery at St. Juan, France."

His grave location is Plot B, Row 19, Grave 218.

"He was my close friend," says Cook. "He had just a fine, wonderful sense of humor. He was modest. Sharp. Never had a nasty word for anyone. He always had pep. He was spirited, loyal. He was everything wonderful you could think of."

The Princeton Alumni Weekly announced his death "with the deepest regret."

The 1943 Class Notes section said this five weeks later:

"With his loss, the Class of 1943 will lose one of its finest members. Those who live their lives at the fullest extent, as did Ty, make America what it is today and leave Princeton with the memory of their greatness."

The oldest Campbell brother, also named Bruce, flew fighter planes in the Pacific before coming back to work in the family business. The two younger brothers, McLean and William, would both go to Princeton, and in fact William would be a goalie for the lacrosse team who would make 28 saves against Army in 1954 and 30 saves against Army in 1955.

All three brothers would live into their 70s.

"Tyler's death was such a blow to their father," Hughes says. "They say he never got over it. He would never talk about it."

As for Tyler Campbell, he was gone, but he was hardly forgotten.

Nearly 14 years after his death, his roommate from his first two years at Princeton, Edwin Baetjer, gave a sermon about Campbell.

"You are perhaps wondering why I am telling you about Tyler Campbell today," Baetjer said. "The answer is this: He is without question the finest person I ever knew; he was my roommate in college for two years at college; and today, the 31st of March, 1958, had he lived, would have been his 36th birthday."

Even today, men nearing 90 are moved to near tears when talking about someone they knew briefly all those years ago.

"There never was a better person," Cook says. "He was a saint."

In 1962, 18 years after Tyler Campbell was killed, the Campbell family created Campbell Field, a grass field next to Palmer Stadium. It sits directly next to Finney Field, where the men's lacrosse team at one time played its home games.

For the most part, Campbell Field has been a forgotten field through the years, a place to walk across on the way to the baseball field or a practice field for soccer, football or lacrosse.

For years it sat in the shadow of Palmer Stadium, and today it sits quietly as the even-larger Princeton Stadium has taken its place. Less than a decade after it first came into existence, Campbell Field saw the construction of Jadwin Gym about 100 or so yards away; DeNunzio Pool rose even closer nearly 20 years after that.

Driving into the parking lot in recent years, attention is directed away from Campbell Field to the huge facilities all around it. Perhaps the only way it's even noticeable now is because both Finney and Campbell were recently converted to FieldTurf from natural grass, and the bright green surface does catch the eye, if ever so briefly.

Stand outside the gate and ask those who park their cars next to it or the athletes who practice on it what the name of the field is, and how many would know? And of those who do know it is Campbell Field, how many know who Campbell was?

How many would know that he was a young man, 20 years old, who made the decision to walk away from studying chemical engineering and playing three sports at Princeton, who made the decision to walk away from an Army desk job, who made the decision to put himself in danger during a war, who twice was wounded and who came back both times because he felt that it was the right thing for him to do at time?

Who would know that Campbell Field is named for Tyler Campbell, who died on Sept. 21, 1944 at the young age of 22 years old, a lifetime of unimaginable greatness denied him in sacrifice to his country's freedom?

Who would know that this field is named for a genuinely heroic figure, a person well worth learning about? Talk to the people who knew him, read what they wrote about him. And emulate him.

Would they know that any field named for Tyler Campbell, Princeton Class of 1943, is to be considered sacred, hallowed ground?

- by Jerry Price