Princeton University Athletics

Feature Story: A Study In Toughness

November 18, 2021 | Football

Tavaris Noel didn’t hear the question. Or did he? What he says – “excuse me?” – doesn’t offer any clarification at first glance.

Does he mean “excuse me,” as in “I didn’t hear the question?” Or does he mean “excuse me,” as in “of course not; how could you even suggest that?”

The question in question is this: “Did you ever think of giving up football?”

In reality, it was pretty clear that he didn’t hear the question. If you talk to him for five minutes, you realize two things about Tavaris Noel: first, he’s way too polite to answer a question that way and second, he doesn’t quit anything.

“Tavaris is a warrior,” says David Harvey, a Princeton football teammate. “He’s the most courageous person I know.”

“Without a doubt in my mind, he is one of the strongest and most humble people I have ever met,” says Sultaan Shabazz, another teammate. “I am beyond fortunate to call him my friend.”

If anyone could ever have been forgiven for giving up a sport, it would have been Tavaris Noel. Now a Tiger senior, he has endured way more than his share of adversity. In fact, few college athletes have ever been dealt the hand he has.

So, yeah, the answer to the question could very well have been the incredulous “excuse me?” Instead, this was what he actually said when the question was repeated:

“I never considered it.”

* * *

In the fall of 2017, Tavaris Noel was a Princeton freshman football player whose college career was just beginning. It was all in front of him – a chance to play football for the Tigers and to study Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at the No. 1 school in the country.

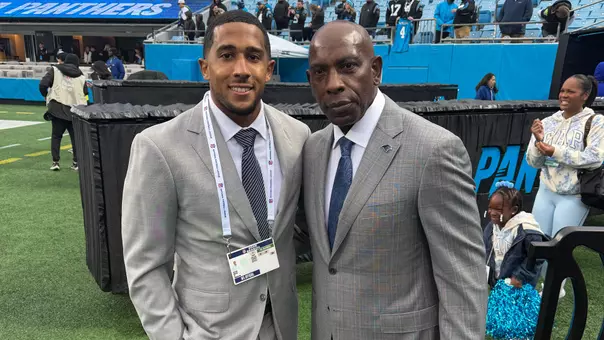

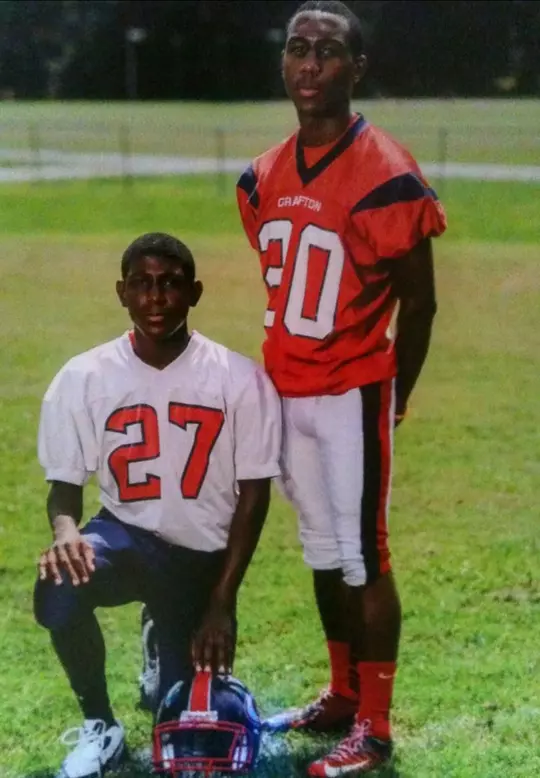

He grew up near Virginia Beach in the town of Yorktown, which is most famous for being the site of Cornwallis’ surrender to George Washington in the Revolutionary War. The younger of Helen and Irwin Noel’s two children, along with his older brother Tyrell, Tavaris was a soccer player as a kid and a good one; goal-scoring was his strength. By eighth grade, though, he wanted to try the sport his brother played and would go on to play in college at Christopher Newport, football

At first, he was all over the place on the field. By the time he got to Grafton High School the next year, he’d started to figure out how to play the game. He was a defensive back and wide receiver, and he’d make 92 tackles as a junior and 112 as a senior.

While he was developing into a football player, he’d always had a love of engineering. It grew out of his father’s propensity for taking pretty much anything apart and putting it back together. That, and how much fun he’d had as a really little kid playing with Legos.

To combine the two pursuits, he chose Princeton.

“I knew I wanted to do engineering which was one of the things that drew me here,” says Noel. “I liked that it was close enough to home that my parents would be able to drive to the games. Once I got on campus and met the people, I knew this was the right place for me. It was a family, and that led me to my decision to come here. It was a family environment, and that was the best fit for me.”

At the time, he had no idea just how important that family environment would be for him. It started to become abundantly obvious with, of all things, an itch. And then another. And then a seemingly endless supply of them.

“I physically felt fine,” he says. “I just had these itches. I was scratching all the time, in random spots. But I never really thought anything about it.”

Then he saw a doctor. Suddenly, the unexplained itching and an unbelievable explanation. Noel, a seemingly indestructible college athlete, was told something impossible to comprehend.

He had cancer. A 6-1, 230-pound sculpted linebacker, and he had cancer.

“They biopsied my lymph nodes,” he says. “Then my parents at me down and told me I had Hodgkins. I didn’t even know enough at the time to know what it was all about.”

How he handled it speaks volumes about who he is.

“Cancer never had a chance against him,” says Tyler McDonald, another Princeton teammate.

“My job was to make sure my parents knew I was okay,” Noel says. “I told them I wasn’t really all that worried about it. If this was the plan for me, then I’d just have to go along with it. I couldn’t spend time thinking about something I couldn’t control.”

At first, Noel didn’t want to mention that he was sick.

“Tavaris was the first friend I made at Princeton,” Harvey says. “During freshmen camp we made a pact that we’d look out for each other. We had an agreement to ensure that the other was awake for early morning practices or meetings. Midway through the season, he didn’t show up a few times even though I texted. The coaches oddly weren't going ballistic. Instead, they each came up to me to ask, in sort of hushed, really concerned tones, how he was doing. I was perplexed, because I thought Tavaris was fine. When I spoke to him later in the day, I told him how serious the coaches were when asking about him. I said “It was like you had cancer or something,” and he said that yes, in fact, he did have cancer. I didn’t believe him. I thought he was going along with the joke, and it wasn’t funny. How could this young, physically fit guy be sick? It’s not possible. And if he did have cancer he would have told me. But I think I knew it was true, because Tavaris is a man of integrity. He didn’t want to make a big deal about it. He didn’t want me to be worried or bothered by it. Once I got over the shock, I marveled at his calm, and at his desire to put me at ease when he must have been terrified. I know I was terrified.”

This wasn’t an easy moment by any stretch. Here he was, far from his Yorktown, Va., home, with a terrible diagnosis. What did he do? He would turn to the community he was just becoming a part of – Princeton football – or maybe that community came to him first.

“I was in a new place, and I didn’t really know anyone,” Noel says. “This was big news I was receiving, just after getting to college. When I was feeling down and by myself, it was my teammates who helped me, lifted me up. Kurt Holuba and Chad Kanoff [Princeton senior captains at the time] came to visit me and told me that they were there with me, that the team was there to support me. Being able to be around my teammates, they were pretty much family to me already.”

He’d need a bone marrow transplant and then eight rounds of chemotherapy, which he started in November. He had a port in his chest the entire time.

“Despite the strenuous chemo treatments, he remained positive and carried a smile any time we come to hang with him during a session,” Harvey says. “He is such an inspiration to me and to his teammates. He went through these grueling treatments like a pro and not some kid who just have some life-altering super scary news who also happened to be living away from his family for the first time. In those initial weeks, I didn’t have him there to make sure I was awake. I overslept and had to bear the punishment, but of course that was nothing compared to what he was facing.”

The treatments carried over through the spring. Still, amazingly, he was able to practice through it all, missing only a few sessions that came on the days after a chemo session. Other than that, he was there the whole time.

Once the treatments were completed, he went for follow up tests and a scan. The news was the best it could be. The cancer was completely in remission.

“When we heard the news of Tavaris' diagnosis, I was taken aback and at a loss for words,” Shabazz says. “My teammates, coaches and I all reminded Tavaris that we were going to be with him every step of the way. We were not going to let him go through this alone. Throughout his entire treatment and remission, he maintained his mental and emotional strength. He never let what he was going through affect the other areas of his life. Personally, I had never seen someone at that age exhibit so much composure and faith. It was a fact that he had cancer, but he made sure that it did not become a part of his identity. Witnessing him go through that entire process, that made me stronger as an individual.”

With his health back, Noel was able to devote himself to get back into perfect football shape. By the fall of 2018, he was competing for playing time on a team that would go 10-0. And then, in a preseason intrasquad scrimmage, he tore his MCL. It didn’t end his season, but it did cost him seven weeks. He would be able to get into two games that season, making one tackle.

Again healthy, he was 100 percent ready to go for the 2019 season. He stepped onto the field as one the team’s top linebackers for the season opener against Butler. He’d made two tackles in the game and was going for a third when an awkward plant led to a pop in his knee. It was a torn ACL.

* * *

“Wait, what,” Marissa Hart says in stunned tones. “What?”

She’s still stunned when she speaks again. “Tavaris had cancer?”

A few moments earlier, she was telling the story about the bond that she and Tavaris Noel share. Hart is a starter on the women’s soccer team this year. Her team has been nationally ranked most of the year, and she and her teammates have reached the second round of the NCAA tournament to take on fourth-ranked TCU.

This year has been a dream for her. The 2019 season wasn’t quite the same. In a game against Dartmouth, Hart was dribbling down the left side and crossed the ball like she’d done hundreds of times before. This time, as she planted on her left foot, she felt a shift and went down. As she tried to stand up, she sensed something was off. The athletic trainer did an ACL test and could tell something was wrong.

“I asked him if I could go back in the game if I could sprint down the sideline and back,” she says, this time laughing. “I came back and said ‘yes, it’s completely normal.’ The coach said I wasn’t going back in anyway, and then I said, to be completely honest, it felt weird and unstable.”

Her ACL was in fact torn. Her path back to the soccer field would start with surgery. As it happened, her surgery was on the same day that Tavaris Noel had his.

“He’s my surgery date buddy,” she says.

Together they would rehab their knees in the Caldwell Field House training room. They would work out together several times a week, pushing each other to get back on their respective fields.

“Going through something like that, with a long recovery from an injury, can be so emotionally draining too,” she says. “Seeing a familiar face who was doing it at the same time I was really helped with the mental piece for me. We used to joke a lot. Can you squat yet? I told him when I ran for the first time and he was so happy for me. He was genuine too. He hadn’t been able to yet. We would joke around a lot. That’s the part of the process that I’m thankful for, that Tavaris was there too.”

Rehabbing isn’t a joking matter of course.

“He has the highest pain tolerance,” she says. “It was so painful the first time they moved my kneecap around. He just sat there stone-faced when they moved his. Nothing was going to stop him. He just puts his head down and grinds.”

Through all their time together, though, Noel never let on that he had previously beaten cancer. That news startled Hart.

“That makes so much sense,” she says. “I had no idea, but that makes so much sense. He’s really amazing. He’s so humble.”

* * *

Like his surgery date buddy, Noel also made it back from the knee injury. The next obstacle was the Covid pandemic, which for him actually turned out to be a positive in terms of getting back to Princeton.

“I hadn’t been able to play freshman, sophomore or junior years,” he says. “I made sure I wouldn’t have any more knee injuries. I worked on my flexibility and mobility, especially my lower body. When I came back, I was confident the preparations I’d done during the Covid year made me healthy as possible, the healthiest I’d felt body-wise.”

He’d worked and worked out at home, returning to Princeton in the summer for more workouts with his teammates. This season he has been a solid backup, getting about 15 snaps a game and totaling eight tackles with one sack. His story is one of perseverance, and it’s also one of the brotherhood that is Princeton football.

“We pick each other up when we are down, and no one is bigger than the team,” McDonald says. “Every guy on the team knows he has 120 brothers who will always pick him up when they're down. Tavaris is one hell of a guy, and I couldn’t be prouder to call him my teammate.”

This Saturday is his final football game. It’s not just any game. A win over Penn at Franklin Field would give the Tigers another Ivy League championship, and it would be the perfect way for Noel to end his career.

It would be on his terms, not on the terms set by fate, which to him has been cruel.

“I cherish every play,” he says. “Every play I go in, I think to myself that I have to make the most of it. Everything has been going well. If this has been the journey that I’ve had to take …”

He doesn’t finish the sentence.

He doesn’t have to.

– by Jerry Price

.png&width=24&type=webp)