Princeton University Athletics

Feature Story: The Unlikeliest May Star

June 02, 2021 | Men's Lacrosse

It’s 5:15 in the morning. Pancho Gutstein is up early. He’s always up early, what with two kids under the age of 3. This is his chance to get to the gym.

He’s in Australia, on the other side of the world. It’s been 25 years since Pancho Gutstein played out of this world in the NCAA men’s lacrosse Final Four. Those who were there with him, his Princeton men’s lacrosse teammates and coaches, still think of him as being from another world.

“Pancho?,” laughs Jesse Hubbard, who scored the game-winning goal in overtime on Memorial Day 1996. “He’s a unique guy.”

“If anything,” says Jon Hess, who along with Hubbard and Chris Massey formed the all-sophomore attack unit that would lead Princeton to two more championships, in 1997 and 1998, “Pancho has become more of a character through the years.”

“He’s quirky,” says Patrick Cairns, the goalie who maybe more than anyone else can appreciate what Pancho Gutstein meant to the 1996 Tigers.

“He has big feet,” says his head coach Bill Tierney.

Yes he does. Size 14s.

“If I had size 12s,” Gutstein says, “we would have lost.”

In all of the glorious history of Princeton men’s lacrosse, through all six of its NCAA championships and 27 Ivy League championships, there has never been a more unlikely hero than Pancho Gutstein in his senior year of 1996. Lacrosse aside, Gutstein was back then and still is today, even 25 years older and a world away, all the things his teammates says he is. He is funny. He is quick-witted. He is laid back.

Make no mistake, though. When Tierney called his name and Princeton needed him most, he came through in a way no one might have expected, and did so on the biggest stage in his sport. It is because of him more than any other single player, even Hubbard who scored the game-winner, that Princeton won the 1996 NCAA championship.

Going even further, maybe if Princeton doesn’t win in 1996, the way it won, it doesn’t win in 1997 or 1998, let alone both. Regardless of such historical guesswork, it is an indisputable fact that Princeton remains the last team to win three-straight NCAA men’s lacrosse championships. That fact would not be true had it not been for Pancho.

“Did he talk about “one shoe?” Hess asks.

Yes. He did.

The NCAA Final Four used to feature a banquet the night before the semifinals, and each of the four participating schools would have one of its players give a short speech. These speeches were fairly standard boilerplate, filled with “thank yous” and “we’re excited to be heres.”

Princeton chose Pancho Gutstein to be its speaker. And why not? With his personality and natural gift for communicating, he was the perfect choice. When it came to Pancho Gutstein, there was no such thing as standard boilerplate, and so the legend of “one shoe” was born.

One of his teammates bet him that he couldn’t work the words “one shoe” into his speech. That seemed easy enough to do. “I was in practice one day, and one of my shoes came off, but I didn’t want to let me teammates down, so I played with ‘one shoe.’” Easy, right?

Uh, no. That’s not what Gutstein did.

“He made up a Spanish poet,” Hess says. “He literally wrote an entire poem, and then in his speech, he said ‘to quote the great Spanish poet ‘Juan Shoe,’ and then he read from the poem he had actually written.”

That light-hearted moment figured to be his one and only contribution to Princeton’s performance at the Final Four. He was going to spend the games themselves as the team’s backup goalie, doing what he always did, supporting his teammates.

“You can’t ask for a better teammate,” says Cairns, who was the starting goalie. “He was the best teammate. He was the person who was the most supportive of me. The way I put it is that when you make a big stop at the end of a quarter, all of your teammates come out and hug you. If you gave up a goal at the end of the quarter, Pancho would come out and hug you. He would be the first one. Always.”

* * *

Daniel Gutstein is the youngest of five children. And by youngest, he’s the youngest by a matter of minutes.

He is one of a set of twins, boy-girl twins. The girl of the set is Abigail Gustein, who was born a few minutes before he was. Abigail was a great athlete at Princeton, a field hockey and lacrosse player who was All-Ivy in both and a two-time first-team All-American in lacrosse. She helped Princeton to the 1994 NCAA lacrosse championship.

“My brother is one of the greatest people on this Earth,” she says. “He is incredibly caring, empathetic, thoughtful, giving, funny, creative and within reason a risk taker. I could go on and on. Like all of us, he isn’t perfect, and he’s has learned from all of his experiences. The love he has for his entire family and his friends is never ending. People have always flocked to him because he has an energy around him that draws people to him. He never judges people, and he listens better than anyone I know. Whenever I get the chance to tell people about him, I cannot stop myself. The older we great the more grateful I am that I am into this world with a teammate – some would say wombmate – and feel very lucky that he is my twin.”

For a very, very short while, it seemed like she was going to be youngest one in the Gutstein family.

“My parents did not know they were having twins,” he says. “My sister was born, and then the midwife said ‘hey, there’s another baby in there.’ So they had to come up with another name, and my dad wanted to name me ‘Pancho.’ He was a big tennis fan, and there was Pancho Segura and Pancho Gonzalez when he was younger. My mother said ‘no way.’ So Daniel was the name they gave me, but my dad asked my brothers Adam and Jono and my sister Sarah what they thought of Pancho, and they liked it, so they all called me Pancho from the beginning.”

“We were very protective of each other,” Abigail says. “Our parents had us in the same crib at first. They told us when they put us in separate cribs in separate rooms, we started to cry. Once they moved the cribs so we could see each other across the hall, we stopped crying. To me that was an example of how close we are.”

The family grew up in Armonk in Westchester County, outside of New York City. Pancho grew up to be tall and athletic, first as a goalkeeper in soccer. He played attack and midfield in lacrosse growing up, and when the high school goalie quit, the coach suggested he jump in cage, since he was already a goalie in a different sport.

“My sister was by far the better athlete,” he says. “She was much more gifted and talented than I was athletically. I’m very proud of what she accomplished. She was always someone to run around with when we were younger. Then, when it came time to go to college, we definitely wanted to go to the same school. She got me into Princeton. They wanted her, and so they also took me.”

Pancho came to Princeton for the 1993-94 academic year. Princeton’s goalie then was Scott Bacigalupo, perhaps the greatest goalie of all time. Bacigalupo led Princeton to championships in 1992 and 1994, winning tournament Most Outstanding Player both times. At the same time, Princeton needed a backup, mostly someone to stop a lot of shots in practice. Gutstein was happy to be there, just to be a part of the team.

“The competition for backup goalie was hang a piece of wood on the goal or me,” he says. “It was very close. Actually, the team was very accepting of me. I didn’t realize how lucky I was. I had limited background and skill, but I had the opportunity to be a part of a team that would win the national championship. That’s a very special thing for me. I got to play against those guys every day, guys like Kevin Lowe. And they made me feel like I a part of it. Regardless of playing time, everyone was in it together. That was T’s culture. I loved practices. I loved competing. I made some saves in practice that weren’t really saves. They were more like guys were aiming for my thigh. Mostly, I got to watch Scott every day. Nobody played goalie like he did. He was technically great. He redefined what it meant to be a goalie. I got to learn from him.”

Without Bacigalupo in 1995, the job was won by Cairns, who would be a three-year starter. Gutstein, who calls Cairns “clearly the better goalie,” was again the backup.Princeton reached the 1995 quarterfinals, falling to Syracuse.

Before the 1996 season, Gutstein was voted by his teammates to be one of the captains, a rarity for someone who had so little playing time to that point of his career.

“Being named a captain was a shock to me,” he says. “It felt good to be named to that role. To never have really played a lot and receive that honor was very meaningful. It reinforced for me to continue to play my role. I enjoyed it. I got to play with the best players in the country. I really did enjoy that, to see what I could do to compete with them. I enjoyed the process. That was my focus.”

“He saw a lot of shots in practice,” Hubbard says. “The shooters became familiar with him. We developed a relationship that way. He’s a great guy. He was a great leader for us.”

The 1996 season began with some changes, including moving Hubbard from midfield to attack and inserting high school All-American attackman Lorne Smith into a deep midfield corps as a freshman. The Tigers defeated Hopkins 12-9 in the opener and then lost to Virginia 12-9 in Week 2 in a game that Virginia led 11-2 at one point.

The Tigers rolled through the Ivy League at 6-0 and entered the NCAA tournament at 11-1. The quarterfinal game was a 22-6 win over Towson, and Gutstein got his first NCAA experience in a mop-up role there. That brought on Syracuse in the semifinals, at Maryland’s Byrd Stadium.

Princeton led 5-1 after the first quarter and 7-3 at the half. The Orange, though, stormed back, tying it at 8-8. The Tigers went up 9-8 early in the fourth, but Paul Carcaterra, a Syracuse midfielder and now an ESPN announcer, tied it at 9-9 with 12:04 to go. Cairns had made nine saves and allowed nine goals to that point.

The decision to make a goalie change is never easy. Doing so in the fourth quarter of the national semifinals is pretty much unheard of, and that doesn’t even include the lack of experience for the player inserted.

“I wish I had the nerve now that I had 25 years ago,” Tierney says.

Whether he does or not these days as the Denver coach, he certainly did in 1996. With his starter struggling and the national semifinal tied in the fourth quarter, he played a hunch. He took out Cairns, and he and assistant coach Dave Metzbower inserted Gutstein. Now, instead of making jokes about phantom Spanish poets, things were really serious.

“At one point, Metzy looked at me at said ‘be ready,’” Gutstein says. “I said ‘for what?’ Then I started to think ‘okay,’ and I was definitely nervous. Actually, I was scared, without a doubt. There were a lot of people in the stands. I remember going into the goal and almost feeling frozen. The first shot they took ended up in my stick. I couldn’t have gotten out of the way of it if I tried. It wasn’t a testament to me, that’s for sure. I was as surprised as they were. But it relaxed me. It was very helpful.”

“Patrick was a good goalie,” Tierney says. “He’d had a really good year. But we felt like he was starting to tire a bit. Metzy and I made decision that if it starts to go bad, we’d make a change. The option we had was an enthusiastic big guy who could get in front of the ball. It wasn’t Patrick’s fault. We just thought we needed a change.”

He was right. Gutstein’s save picked up the entire team. Within a minute, Princeton had scored twice, with goals from Ben Strutt and Massey. It was 11-9, and it stayed that way. Gutstein made three more saves, giving him four without allowing any. Princeton was on its way to the final.

“I remember the national semifinals against Princeton like it was yesterday,” Carcaterra says. “In came Pancho, and we thought we had the game won. Well, I was certainly wrong. He stood on his head and made a handful of incredible saves in the fourth quarter of that game. Princeton went on to win the championship, one of three straight. In 1996, without Pancho I am not sure that happens.”

With that win behind him, Gutstein was on his way to the postgame interview room. He was typical Pancho there. Specifically, he was asked about the origins of his name. Without skipping a beat, he said that he was a combination of a mother who was half Mexican and half Cherokee and a father who was Prussian.

“I was just having fun,” he says. “I may have been being a little punk. I do know that I gave the credit to the guys who were playing in front of me because honestly they were the ones who deserved it.”

For the championship game, Cairns was back in goal. The opponent was Virginia, the same team that had dismantled Princeton back in March. If Princeton’s attack of Hess, Hubbard and Massey was as good as any that has ever played the game, so too was Virginia’s unit of Michael Watson, Doug Knight and Tim Whiteley.

Princeton led 6-5 at the half, but UVa scored the first two of the second half. Cairns had made four saves to that point. This time, the call to Gutstein came with less than three minutes gone in the third quarter.

“It was sub-optimal for me, but Pancho was playing really well,” says Cairns, who rebounded the next year to become an All-American and an NCAA all-tournament team selection for the unbeaten 1997 team. “He was the senior. If you look at 1996, Hess, Hubbard and Massey did Hess, Hubbard and Massey things. If you think about why we won, it was seniors who rose to the occasion. Seniors, who don’t have another season, tend to dig down a little deeper. It was guys like Pancho. I couldn’t have been happier for him.”

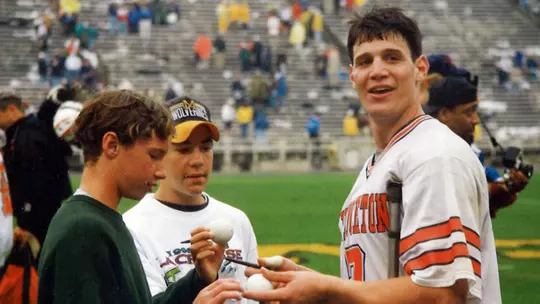

Gutstein made eight saves while allowing five goals against that attack the rest of the way. Princeton won 13-12 in overtime. Gutstein made the All-Tournament team.

Abigail Gutstein was in the stands that weekend. Her own career had just ended a week earlier with a 6-5 loss by the Princeton women in the semifinals, leaving her with one national championship, four Final Fours and three championship game appearances in addition to her own two first-team All-American honors.

“I remember it being very emotional for me to see him crushing it,” she says. “He had worked so hard and to see him rise to the occasion and have his moment in the sun was and still is a highlight of my college athletic career. For me it was like winning again. It was the epitome of perseverance, resilience and true teamwork. I remember Pancho talking about what a great group of teammates he had, that everyone was out for the good of the team and not for individual glory. The each knew they were a part of a puzzle that to be complete needed them all. I think when Pancho when into the game, everyone was confident that he would deliver because that is what that team did and because they fed off of one another. It’s a story I still tell people because it inspires me.”

“It still feels surreal,” Pancho says. “Patrick was the starter. He’d gotten us there. I was a practice player, that’s all. I really don’t feel like I had a lot to do with it. The guys in front of me, they did all the hard work. And I got so lucky. They took one shot that hit my foot. I’m a size 14. If I’m a size 12, it goes in.”

It was more than that. First, a goalie change, like a quarterback change, always sparks the rest of the team. Second, there was the personality of this goalie.

“Pancho is the kind of guy who makes a difference,” Hess says. “He’s gutsy. He has a lot of confidence. His personality is so robust and lively, and that can translate. We’re playing one of the most electric attack units ever put together, and all of us were just praying the ball wouldn’t go into the back of the net. For him to step into that, it was so gutsy. He relied on a ‘screw it’ mentality. There was everything to lose. He made some saves that were classics, doing everything he had to do to stop it from going into the back of the net.”

The game-winner in OT came after Princeton won the face-off and called timeout to set up a play to Hubbard. Jason Osier set a pick for him, and Smith delivered Hubbard the ball. Hubbard’s shot bounced on the wet turf on a rainy day and into the goal, giving the Tigers their third title.

“I remember clear as day what I said to Jesse out of the timeout,” Gutstein says. “I told him just ‘end this. Please.’”

Pancho Gutstein graduated in 1996 and tried to pursue acting in New York City. After that he got into marketing, with Graco, a company that makes baby products.

“I had no talent as an actor and didn’t have a thick skin,” he says. “It was a bad combination. And what did I know about babies then? I was in my 20s. Babies weren’t on my mind. But I used to wear Pumas to work all the time. One of my mentors asked me what I wanted to do next, and he said I should work for Puma. I was fortunate enough to get a job with Puma in Boston. Then after seven years in Boston, this opportunity in Australia came up. I’d played lacrosse there the summer after my sophomore year and loved it and Kay had always dreamed of living there.”

He and his wife Kay, whom he’d met during his stay in Boston with Puma, jumped at the chance for that adventure. Today he is the general manager for Puma’s operation in Oceana, overseeing the company’s business in Australia and New Zealand. Since they arrived there in 2017, they’ve had two children, both girls, Isla Grace and Florence Rose.

“I am very grateful for the chance I had to have been on the team at all,” he says. “That was very special and really should not have happened to someone with my lacrosse background. The way it all played out, it was a lot of good fortune. Had it gone the other way with UVa in the overtime, it would have all been very different, and it certainly could have happened that way. I have so much gratitude. This is a much better ending to my lacrosse story.

He is so many miles removed from Princeton now, but he is hardly forgotten by his teammates and coaches. They all remember him as the big, affable one who was a great teammate and who stepped into what was a really difficult situation and thrived.

Princeton lacrosse history remembers him for one of the single greatest individual performances the program has ever seen, turned in by one of the single most unique individuals ever to be a Tiger.

by Jerry Price