Princeton University Athletics

Feature: A Story Of Three Generations

January 28, 2022 | Men's Basketball

The bicycle showed up on their doorstep, a gift from the mother of one of the eight roommates. It sat in a box, waiting for its new owner to return from a class. It was brand-new, shiny, flawless. For one of the roommates, it was just too tempting of a target.

And so he went to his own bike, an old beat-up one at that, and took the lock off. Then he went into the box, attached the lock to the new one and sealed it again. When the roommate came back and opened it, he loved everything about it – except that he couldn’t find the key to unlock it. He searched the box. He turned the room upside down. He called his mother, who said she knew nothing of a lock or a key.

For one day, for two days, the other roommates didn’t let on. Finally, they let him in on the joke.

“We were all accomplices,” says Bill Agnew, one of the group of eight who lived together that year, “but we weren’t the ringleader. There was only one ringleader, and he had a gleam in his eye.”

The year was 1955. The ringleader was John DeVoe.

* * *

It’s a dreary January day in Hilton Head, S.C., which means it’s one of those rare days where Bill Agnew can’t play golf.

“I played yesterday,” he says. “Now it’s in the 40s.”

He settled here 25 years ago, after a long, successful career in business. He is a 1956 Princeton graduate and a 1958 graduate of the Harvard Business School. That he’ll turn 88 this April does not stop him from having great recall of his Princeton days, from which he can tell amazing stories, such as what it was like to play football for Hall-of-Fame coach Charles Caldwell.

“He was terrific,” Agnew says. “He pitched for the Yankees at one point, you know. His wife would bake us a cake after a game if she liked how we’d played. Sometimes we’d win, but we still wouldn’t get a cake. That’s when we knew we had to be better. Charlie died in his 50s from cancer. It was terrible. But his wife became a close family friend. She was the godmother of our oldest daughter.”

Agnew was a wingback on offense and a halfback on defense on Caldwell’s teams of 1953, 1954 and 1955, back when Princeton was still playing the single-wing with two-way players. A sprint champion in high school, he was tall at 6-1 for a wingback, which earned him a nickname from his running backs coach.

“He’d say that wingbacks were supposed to be unseen,” he says. “They’re supposed to be little guys who could sneak around the end. He used to call me ‘the lighthouse.’”

Agnew’s springs were spent playing first base for the baseball team, where he played for another legendary Tiger coach, Eddie Donovan.

“I won the award for the highest batting average,” he says, “but one night the coach said ‘don’t make me tell them what your average was.’ We weren’t a great hitting team. I got a lot of bunt hits, infield hits. Every now and then I’d get a solid hit.”

The football teams he played on went 17-9-1, including 7-2 his senior year, when the captain was future Director of Athletics Royce Flippin. Those Tigers were 6-1 against teams that the next year would compete for the first official Ivy League title, with the only loss among them in 1955 by a 7-6 score to Harvard.

“My roommate at Harvard Business School was a guy named Bill Crosby,” he says. “We called him ‘Bing.’ He was the guy who kicked the extra point against us for Harvard. He was a great guy who became a great friend, but when I went to visit him, his parents had the shoes he kicked the extra point with over the fireplace.”

Agnew grew up in St. Louis, the son of a banker. He’s from a Princeton family, that’s for sure. He has two younger brothers who went to Princeton, Gates from the Class of 1957 and Hewes from the Class of 1958 (Hewes served as a member of the Princeton Varsity Club Board of Directors and has remained a steadfast supporter of Princeton Athletics). Just like their own father, Bill, whose real name is Franklin, sent three children of his own to Princeton.

He’s happy in Hilton Head. He and his wife originally moved to Spring Island, a small community near Hilton Head where “you could have a cocktail party and invite everyone who lived on the island.” Even from that distance, he has stayed close to his alma mater, and his lifetime of loyalty to Princeton includes having spent 14 years as a trustee.

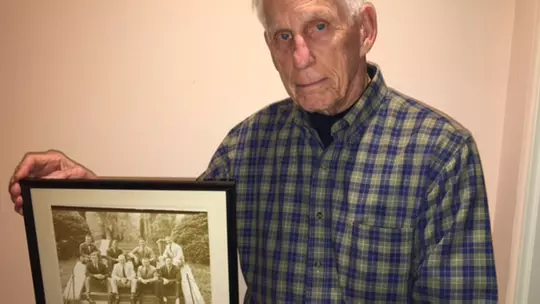

Perhaps his fondest Princeton memories are from the suite in a dorm called Joline, in which he lived as a junior, where he and seven others shared two sides connected by a common area. He still has a photo in his home of the eight of them. Some were athletes. A few have passed away. Some had nicknames, like “Doc” and “Cosmo” and “Smiley.”

The eight men in the picture were Agnew, Charlie Obrecht (who was the captain of the lacrosse team), Ralph Stuart (captain of the tennis team and the one whose bicycle it was), John Murdock, Tim Orvald, George Callard (wrestling captain), Dave Mohr and, of course, the aforementioned practical joker, John DeVoe, who was the captain of the basketball team.

While Agnew has lived a long, full, rewarding life, that was not to be John DeVoe’s destiny. Instead, he passed away on Dec. 14, 1968, when he was just 34 years old, dying suddenly from an undiagnosed heart ailment. He was the president and part owner of the Indiana Pacers, then in the old American Basketball Association (the one with the red, white and blue striped basketball and the original three-point shot). John DeVoe left behind a wife and three young children.

Now fast-forward a little more than 53 years, to January of 2022. Bill Agnew was watching an episode of “Hard Cuts,” the weekly video series that highlights the Princeton men’s basketball program.

“I was watching one of the clips,” he says, “and I saw him. I stopped right there and said ‘Oh my God that’s John.’ He looked like him. He moved like him. It was John.”

It wasn’t John, of course, but it was the next best thing. It was John’s grandson.

* * *

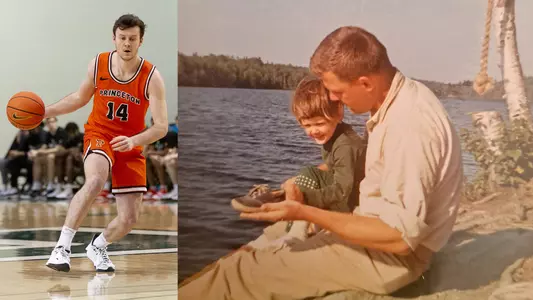

Ethan Wright knew he was getting more than his share of rebounds during Princeton’s men’s basketball game against Minnesota back in November, though he had no idea what the actual number was. Then he saw the statsheet when the game was over.

“I thought I had a bunch,” he says. “Then I saw after game. It said I had 18. Eighteen? I was a bit shocked.”

He hasn’t matched that number since, but he’s consistently pulled down rebound after rebound. He’s had 10 other games with at least seven, including five in double figures. He is averaging nearly eight per game, which leads Princeton and ranks fourth in the Ivy League. The three players ranked above him in the league stand on average 6-7 and weigh on average 225 pounds. Wright is 6-4, 190.

When you watch him play, you can’t help but be struck by the fact that he always, always seems to be in the right place at the right time as the ball comes off the rim. When the ball is loose, No. 14 just seems to appear.

“I can jump,” he says laughing. “I’m a little more athletic than people realize. Being able to go and get the ball has been fun. It’s been a focus of mine this year. I am a bit on the smaller side, but we emphasize having guards who can rebound. My teammates make things easy for me. I just have jump and get it.”

In addition to being fourth in the league in rebounding, he is also eighth in the league in scoring, averaging 14.5 per game. He is one of the biggest reasons why the Tigers enter their game at home Saturday against Yale unbeaten in the league.

“We’re really enjoying playing with each other,” he says. “We’re playing with confidence, and we’re hopeful for the rest of the season.”

Wright is a senior, one who has gotten consistently better throughout his career. He more than doubled his scoring average from freshman year to sophomore year and has done so again from sophomore year to now, going from 3.5 to 7.2 to 14.5. His rebounding total has doubled from sophomore year, going from 3.8 to 7.6 this year.

“I love it,” his first AAU coach says. “He’s always been a crazy jumper. Rebounding was always a big focus of my coaching, but I do think rebounding is about a lot of grit.”

Rebounding was also a big focus of the coach’s game as well. As a Division I player, at Princeton no loss, this particular coach finished with 942 career rebounds, a figure topped by only four other Tigers. There were three separate seasons when Wright’s AAU coach averaged at least nine boards per game, finishing with a career average of 9.7 and a career-high of 23 in one game.

And who was this coach? For starters, the coach is a she. Also, this particular she is more than just his former coach and one of the greatest Princeton women’s basketball players ever. She’s also Ethan Wright’s mother.

Her name is Ellen. Ellen DeVoe. Her father was John DeVoe. Ethan Wright is the grandson who caused Bill Agnew to gasp “Oh my God” when he saw clips of him.

* * *

Ellen DeVoe was four years old when her father passed away. She has an older brother, also named John, who was seven at the time. Her younger brother Tommy was three. Her memories of her dad are fuzzy at best.

“If anything, I remember when he died,” she says. “He used to take us to a restaurant in Indiana called ‘The Huddle’ for breakfast. We were supposed to go there, but instead it was ‘go get your brothers.’”

John DeVoe grew up in Indianapolis and was a big-time scorer at Park School High School, including one game in 1952 where he scored 73 points. He followed his older brother Chuck, a member of the Class of 1952 who was also a great tennis player, to the Princeton basketball team, and his younger brother Steven, Class of 1957, would later follow.

Playing for Cappy Cappon at Princeton, John averaged 4.8 points per game as a sophomore in 1953-54, and he followed that with 12.2 as a junior and 15.6 as a senior, when he served as captain and then won the B.F. Bunn Trophy as the team’s top player. He could have joined the Princeton coaching staff after graduation, but he chose instead to return to his home city, where he worked in insurance and also founded the Indianapolis Racquet Club.

With his business success and love of basketball, DeVoe was the driving force in pioneering a new franchise in a new professional basketball league. The American Basketball Association was a wonderfully entertaining league, known for its wide-open style in addition to its colorful ball and never-before-tried three-point line. The league also attracted a long list of great players, including Julius Erving, George Gervin, Bobby Jones, Moses Malone, Billy Cunningham, Connie Hawkins, Artis Gilmore, Rick Barry, Spencer Haywood, David Thompson, Dan Issel and Princeton’s own Brian Taylor.

DeVoe was able to put together enough partners to buy into one of the league’s original 11 franchises in 1967. The team would be named the Indiana Pacers, and it would win three league titles before being one of four ABA teams to be absorbed into the NBA with the 1976 merger (along with the franchises that are now the Brooklyn Nets, Denver Nuggets and San Antonio Spurs).

The Pacers played their home games at the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum, today the home of IUPUI. It was there, on that night in 1968, about a year after the franchise was born, that DeVoe died, shockingly, suddenly, at courtside, just after a Pacers win over the Houston Mavericks.

“It’s very difficult for me to know if I have actual memories of him or just have stories that family members have told me,” Ellen DeVoe says. “Maybe I have snippets of memories. My brother John has more.”

What she does remember is how some of the Pacers players would come by her house to look in on her mother and the three kids. Eventually, her mother would remarry, to a man named Alan Nolan, a widower himself.

“He’d lost his wife to a sudden death as well,” DeVoe says. “He was incredible. And he had five kids of his own, who are now my siblings. The youngest five are just 18 months apart. We moved into their big house. He was an attorney at a big firm in Indianapolis, as well as a Civil War historian. They cross-adopted us. We’ve grown up to be very close, all of us. We all try to get together at least once a year. Last year, there were six of us there, with various grandchildren.”

Ellen DeVoe would grow to be a shade over 6-feet tall, but her height and her family history in basketball (her uncle Chuck took over as Pacers’ president after her father’s death) didn’t do much for her until she got to high school. To that point, she had played very little, but that changed when Billy Keller, a former Pacer who was on all three ABA championship teams, became the coach at her high school, a school called Brebeuf, which had been all male until just before she started there.

Keller knew who the DeVoe’s were, and he could see how tall she was. By her senior year, she would be a high school All-American. She would also lead her team to the Indiana state finals.

“At the end of my freshman year, he came up to me and said ‘Ellen, you’re the tallest girl in school. And I know about your family. You’re going to play on my AAU team and then on the varsity next year.’ I had incredible coaching in high school. We were a tiny Jesuit school with 500 total kids, and we went to the state finals. We got tons of press. High school girls’ basketball got tons of press. We played in a packed gym, just like the boys. We had a whole team of male cheerleaders. It’s what you think of when you think of Hoosier hysteria.”

By the time she chose a college, she had all kinds of offers.

“My parents wanted me to go someplace where I would get a great education,” she says. “I went through the regular application process at Princeton, and I got in. I said that I had to go, because of my dad.”

She would become a dominant player in the second decade of women’s basketball at Princeton, finishing her career with 1,290 points before graduating in 1986. She still holds the school record for blocked shots in a game with nine against Rider her sophomore year, and she had the school records for points in a game (38 against LIU junior year) and blocked shots in a career before Bella Alarie broke both of them.

She’d also be a four-time All-Ivy League selection, earning first-team honors as a sophomore and again as a junior, despite missing the final five games of the year after tearing her ACL. She’d try to play on it, but it gave way again, leaving her with 999 career points heading into her senior year.

After graduation she would get a Master’s in clinical social work and mental health from Denver and then a Ph.D. in social work and psychology from Michigan. Today she is a professor and associate dean at Boston University, where she is also the founding director of the trauma certification program. Her specialties are trauma and parenting, military families and child maltreatment and gender-based violence.

“To some degree Princeton led me to this,” she says. “I was a history major and in the first cohort to get a women’s studies degree. Princeton introduced me to inequity and injustice. My first job out of college was in a shelter for abused and neglected kids. It was fascinating, compelling work.”

She’d also get married, to a man named Don Wright, who had been a rower at Yale. They had three children, with Ethan the oldest and then another son, Jake, who is at UCLA, and a daughter, Abigail, who is in high school.

“There are too many early mornings in rowing,” Ethan says. “It was always basketball for me. It was always my favorite sport. My mother taught me how to play from a young age. She was my coach until around eighth grade, coaching my AAU team. She taught me how to shoot, dribble, pass. I got to learn a lot from her. A lot of my game is a credit to her. She’s already been a role model and guiding force.”

Wright attended Newton North High School outside of Boston, where he was the Bay State Conference MVP as a junior and senior, when he averaged 26.2 points and 7.2 rebounds.

When it came time for Wright to choose a college, Princeton was the school that was recruiting him the hardest. His mother never pushed him to attend the school where she and her father and uncles had played, but she wasn’t exactly against it either.

“She was pretty excited,” Wright says. “I think it just so happened that the school that was recruiting me from the beginning was Princeton. It was definitely helpful to have a parent who could tell me about the school and experience, but she didn’t push me. She tried to stay in the background, but it was definitely nice to know that she had experienced it.”

* * *

Ellen DeVoe says she could somehow feel her father’s presence in Jadwin Gym, even if he passed away before it was built.

“When I was there, it felt like there was a ghost with me at times,” she says. “I imagined my dad’s experience at Princeton. Every season, there would be three or four times a year when someone from his era would be at a game and they’d introduce themselves and talk about him. That was lovely.”

The same has happened to Ethan Wright.

“There have been some people at games who have said that,” he says. “It’s been pretty emotional. I’ve come off the court, and there have been guys who’ve come up to me and said ‘you play just like your grandpa. You move like him.’ It’s an honor to be compared to him.”

And this is where Bill Agnew’s story overlaps with that of the grandson of his old roommate. After watching that episode of “Hard Cuts,” Agnew decided he wanted to reach out to Wright, wanted to talk him about his grandfather. His brother Hewes connected him to the athletic department, and suddenly Bill Agnew and Ethan Wright were on the telephone.

“I thought it would be fun to teach Ethan a bit about his grandfather,” Bill Agnew says. “He obviously never got a chance to know him.”

So what did he tell him?

“I told him that I think he and Ethan look a lot alike,” Agnew says. “They have the same mannerisms. John had a great set shot. He had good jumping ability. He was also a really happy-go-lucky guy. He didn’t take his work nearly as serious as some of the others. He could disregard convention. You couldn’t help but love him. I told him about the time we went to the Indy 500 together. I told him what a great, wonderful man his grandfather was.”

“We spoke for 30 to 45 minutes,” Wright says. “There’s a lot that I don’t know about him, and that’s why I talked to Bill. I’m learning as much as I can. There’s so much that I want to know. The conversation was great, just to hear from someone who’d lived with my grandpa. He was really excited to talk to me as well, which meant a lot. My grandpa was a big part of his life, and he was excited to talk about his old friend. It was great to talk to someone who had been his roommate.”

DeVoe was moved by Agnew’s gesture. So was her son.

“Ethan was very touched by what Bill did,” she says. “We would like to be in touch with anyone who knew my dad. Bill told Ethan some stories about my father that I’d like him to remember.”

It was Agnew who told Wright about the bicycle prank. He asked him if he was a prankster, and if so, that’s where it came from.

“We’re all pranksters,” Ellen DeVoe says.

She tells the story of the time that one of her brothers set up a series of alarm clocks to go off throughout the night in another brother’s room during a family trip, including several that were placed inside vents (though with a screwdriver on the bedside as a hint). As payback, a rooster made its way onto the first brother’s porch one morning.

“We do a lot of pranking,” she says. “Apparently so did my father. Maybe it’s genetic?”

— by Jerry Price

.png&width=24&type=webp)