Princeton University Athletics

Feature Story: Of Love, Sorrow And Cancer

October 28, 2024 | Women's Soccer

Patricia Driscoll died on Oct. 21, 2018. Her fight — brave, but ultimately unwinnable — had been against ovarian cancer. She was only 69 years old at the time of her death.

Her passing left an unfillable void in the soul of her son Sean, the head women’s soccer coach at Princeton. Sean Driscoll is where he is today because of his mother’s, what, words? Actions? No. That’s not it. Not in this case. This is more of an intangible.

Patricia Driscoll was a psychotherapist. She was brought in to counsel first responders at Ground Zero after 9/11, in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, in Connecticut after Sandy Hook. She was a woman of spirit. She was a woman of passion. She was a woman of compassion. She was all those things.

“Do what you love,” she told her son. “The rest will take care of itself.”

“I told her that I wished I had her compassion for helping people,” Sean says. “She said to me ‘don’t you see that you do?’ After that I quit my job and immediately went into coaching full time.”

My conversation with Sean grew out of a call he made to me about a story idea. Some of his players were dealing with those close to them who either had or have cancer and perhaps they would like to talk about it in a way that would be helpful to share. Plus, October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

“Everybody knows someone who has gone through this,” he’d say.

Sean had no way of knowing just how much his comment hit home with me. I never met Patricia Driscoll. It was almost six years to the day that she had passed away that Sean told me about her. And yet I knew her, or at least someone just like her.

Gail Price underwent surgery in Atlanta on June 17, 1993; her fight was against lung cancer. The surgery brought hopes of removing a tumor that had attached itself to one of her lungs, but it was not successful. In recovery, the doctor said she had between 14-18 months, something that was never shared with her.

She died on Dec. 11, 1994 — six days shy of 18 months later. She was 55 years old. This December 11 will be the 30th anniversary of her passing. She died never having had a cell phone or an email address or ever having used the internet. She has two grandchildren today, ages 27 and 24, and she never met either of them.

Gail Price was my mother. The story that Sean asked me to write? It’s personal, for him, for the players I spoke to, very likely for you — and definitely for me. I am now 30 years down the road, and the void is still there.

Esme Rudell is taking small forkfuls of her chicken Caesar salad at an eatery on Nassau Street. She’ll probably eat about 20 percent of it in the 45 minutes or so we talk and then take the rest to go. It’s not because she isn’t hungry.

It’s because she’s talking about her mother, Kaari Upson. Kaari’s fight was against breast cancer, and it lasted 10 years before she passed away on Aug. 18, 2021. She was 52 years old.

Along the way, she had a double mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation and remission and went from Stage 2 to Stage 4 to metastatic, all the while working as a full-time artist. She also raised a daughter who essentially grew up watching her mother’s illness progress and who was only 16 when her mother died. Kaari would not live to see her daughter play soccer at Princeton University, though she is, just as in the case of her daughter’s coach, the driving reason for why Esme is today part of the Tiger women’s soccer team.

“Her illness was completely intertwined with my soccer career,” says Esme, a sophomore. “She’s the whole reason I’m at this school in the first place.”

Clearly, Esme can talk, and as she does, she spins the wheel of emotions and lands all over, alternating between laughing, sighing, smiling and tearing up. She quite often lifts her fork and then puts it down without taking a bite. Each time she does, the bruise on her left arm is in plain sight. It’s impossible to miss.

“Does that hurt?” I ask her.

“Does what hurt?” she says.

I point to the bruise, which is something of a large turf burn.

“Oh this?” she says. “My mother always said that if you get hurt, you wear it with pride. She’d wear the physical marks of her illness with pride. She didn’t have hair for most of my life, but she never, ever wore a wig. You better be tough, she’d say. I don’t care if you’re not feeling well. You have to be tough. I think I’m a tough, hard, aggressive player, and that comes directly from her.”

Kaari was a soccer player too, one who grew up playing against boys. The first time she played against girls?

“She broke a girl’s leg,” Esme says. As she tells this story, she is a mix of sad for the girl in question but admirable of her mother’s intensity. “I actually had to learn to pull back just a bit. My teammates when I first got here said ‘you are really aggressive.’”

Esme’s father, Kirk Rudell, graduated from Princeton in the Class of 1991 and played soccer with current head coach Jim Barlow and for former head coach Bob Bradley. Her parents divorced when she was three, and she grew up between Los Angeles and New York City. She was only six when her mother was first diagnosed.

Esme attended school in California, where she also played for a very small club soccer team called “Tudela FCLA,” named for the team’s coach. With her mom’s frequent treatments, it would be very much a communal effort to get her to practices and games, between her father and teammates and even the coach, who would drive 45 minutes out of his way, each way, to get her and bring her back.

“The club was my family,” she says. “They were the people who got me through. I never wanted to leave them.”

In the world of soccer recruiting, club teams are way more important than high school teams. So are ID camps, which are individual showcase events on college campuses. Tudela was a very small team without a big reputation, but it did have talented players who were hoping to play in college, possibly even Division I.

The summer of your junior year of high school is huge in the process and for Esme, it wasn’t like that of pretty much anyone else. Her mother left Los Angeles in April to return to New York for what her doctor there called “intense treatment,” but Esme had to stay in Los Angeles for school and for soccer, including going to a tournament in Idaho because without her, the team would have had only 11 players.

After playing as much soccer as she could and trying to get on the radar for as many coaches as possible, she finally did go to New York City to be with her mother. This was in late June. What followed was what she describes as “the weirdest month and a half of my life.”

Consider what she was going through at the time. Her mother’s fight was nearing its end. She was trying to find a college and be part of its soccer program. She was 3,000 miles away from her friends and life in California. And she was 16 years old.

“I knew something was off when I got back to her apartment from the airport,” Esme says. “She wasn’t herself. She was clearly not doing well. She had a doctor’s appointment the day after I got there, and they did some blood work and had to keep her at the hospital. Now I was in the apartment all alone.”

Kaari would come home, but this time it was to home hospice care. Esme, though, flew back to California to play in one more club tournament, a two-day showcase event. Yes, her team needed players, but also yes, she needed an escape. She would be gone for four days.

Then, just around the Fourth of July, she had another opportunity, this time to attend an ID camp at Princeton. Before she left for her first three days ever on campus, though, her mother’s doctor had some difficult words for her to hear.

“So here was little 16-year-old me from a club nobody had ever heard of, trying to get recruited and trying to navigate this thing with my mom,” she says. “The doctor said ‘if you go away now, I can’t tell you what state your mother will be in when you get back. You may be saying goodbye to your mother as you know her now.’ It was a heavy moment, but I had to go and do this.”

Whether it was meant to make a statement or not of where she stood, she was issued the highest number of any player at the camp.

“The first night, we played on turf, under the lights,” she says. “I lit it up. I just felt it. It was the best I’d ever played in my life. I remember walking past Sean and all the coaches and they said ‘Who are you? Where are you from? We’ve never heard of your club team.’ I’m very superstitious. My dad was there, and he knows I do not like to jinx things and that I’m very self-critical. I told him that I knew I had just crushed it. I didn’t know what was going to happen, but I knew I’d crushed it.”

When the ID camp ended, she went back into the city, switching on a dime from the high of playing at Princeton to the low of her mother’s hospice.

“When I came back from Princeton, I had bought a ‘Princeton’ sweatshirt,” she says. “It was a black crew neck that said ‘Princeton.’ My mother was in her bedroom, with two of her best friends. They were all sitting there. It was a summer day, but I was wearing my sweatshirt. I loved it. I was smiling and I couldn’t wait to tell her about it. She looked at me and said ‘You look so happy now. You’re going to go there.’ I was so mad. She’d jinxed it. I said ‘I went to one camp. They don’t even know who I am.’ She said ‘I’m just telling you that’s the place for you.’ I was so mad that I took the sweatshirt off and wouldn’t wear it again until I committed.”

By the time that happened, Kaari had passed away. She had eventually lapsed into a coma, and Esme had to leave to go back to California to get ready for her junior year.

“After all that time,” she says, glassy-eyed, “I really didn’t want to be there when she died.”

A few days later, Ally Murphy is sitting in the same chair at the same table where Esme had been. Murphy orders avocado toast and powers it away. She doesn’t talk as loudly as Esme, or say as many words, but she, too, runs the emotional gamut. Like Esme, she tells stories that cause her eyes to become the same level of glassy, with hints of tears.

As she eats, she talks about her father, Brian. His fight is ongoing; his opponent is prostate cancer. In sports terms, the cancer jumped out to a big early lead, but Murphy has now pulled in front.

Brian Murphy is 51 years old. He spent 17 years as the head men’s hockey coach at Tufts, after he had been a defenseman there as an undergraduate. His 158 wins are the most ever by a Tufts men’s hockey coach, 85 more than anyone else.

“He doesn’t drink or smoke or do anything like that,” his daughter, a junior, says. “He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2018, when he was 45. It spread down into his leg, and technically it is considered incurable. His cancer numbers have come way down, but he’s been affected in so many different ways. He doesn’t have a functioning leg, for instance, because of the radiation. Now he walks with a cane. He can’t walk or run or skate, and he’ll never be able to do so again.”

Ally is the middle of the three Murphy daughters. Her older sister, Mia, went to Tufts as an undergraduate and is now in medical school in Nebraska. The youngest, Ava, is a sophomore on the Lafayette women’s soccer team, whom Princeton defeated earlier this season after tying a year ago.

“My dad says he’ll bring up that tie at my wedding,” she says.

Ally was a high school freshman when her parents — her mother Laurel played field hockey at Tufts — told all three daughters that they had something important to tell them. To that point, maybe the toughest medical issue they dealt with was the torn ACL that Mia suffered that ended her hopes of being a college soccer player as well.

“We have two couches, one for three and one for two,” Ally says. “They sat us down and said they really needed to talk and that it wasn’t good news. Your first thought is ‘oh no, they’re getting divorced.’ You don’t think your 45-year-old dad is going to tell you he has cancer. After he told us, the next thing he said was that it’s a Saturday and you’re going to the high school football game like always. You’re not staying home. You’re going to continue to do what you’re doing, and you’re not going to sit around and worry about this. His first concern was us, even though he was going through something … crazy.”

It was crazier than he let on, actually. It would require all the toughness of a hockey player, and more, to make it to this point. The prostate is measured with a PSA number, and anything over four is considered elevated. His PSA was 200.

“It was horrible,” Ally says. “The doctors that he went to all told them he had to prepare for the idea that this was going to get him. He got opinion after opinion, and finally one doctor said ‘we’re going to get this.’ He told him that he was young, healthy and in shape. He started on two treatments at once and was given higher doses of radiation than was thought possible. He actually was on TV once talking about it.”

It was not easy. He would get up at 4 am on the mornings of his treatments and drive from the family home in Winchester into Boston. He’d be back in time to take the daughters to school, and then he’d sleep all day.

“He’d just be hurting in silence and was a little more private,” Ally says. “I would never look at my dad and think ‘he’s sick.’ I wasn’t able to comprehend it at that age. He does such a good job of keeping things positive, of letting us know that he’s okay. He always says that there are bigger problems in the world.”

Ally Murphy’s recruiting story isn’t that much different than Esme Rudell’s. Princeton was interested? That’s it. You’re going there.

“He was the best through that process,” Murphy says. “The second Princeton walked into the picture, he said ‘you’re going to Princeton. You’d be so lucky to go there. It’s such a great school.’ He wasn’t controlling, but he knew the recruiting process and knew what he was talking about. He was definitely my engine during the process. He’d laugh at me when I’d get overwhelmed by it all.”

She’d play in 15 games as a freshman and zero as a sophomore after a foot injury suffered in the very first minute of the first scrimmage. Eventually, after missing all season, she had surgery this past January.

Coming back from that is not easy. There is the physical piece, the one where you are going through rehab. There is the mental piece, the one where your season is gone before it starts.

“My father would send videos through his rehab after his first surgery,” Ally says. “He had no bone left at all. Radiation had taken it. When I’d have a day in pain or not wanting to rehab because it’s tedious and tiring and painful, he’d remind me how lucky I am. I was at Princeton. I was doing what I love with my best friends. One of the things I have learned from him and seeing him go through surgeries and radiation is that even though you’re hurting, you never complain about being able to get back to a healthy spot. I’ve never seen or heard him complain, even though you know how much he was hurting. That’s the mental toughness he gave me.”

Summer Pierson is sitting on the steps outside of Stanhope Hall, not far from Nassau Street. When I offered her the same chance to sit in the same diner as her teammates had, she said that she’d already eaten.

Pierson speaks very softly, and she pauses to consider her answers to my questions. Her emotions too bounce all over, and she offers an unnecessary apology, because what she is apologizing for is simply not true.

“I’m not great at putting words to my thoughts,” she says.

I consider that, and I reject it. Her issue isn’t putting words to thoughts, at least not in this moment. It’s that the thoughts are brutal ones.

She talks about three people in her life. Her first cousin, Sarah O’Neil, fought her fight against brain cancer. She would lose that fight, 10 years ago, when she was only 15 years old. Sarah’s mother, Shelley, who is Summer Pierson’s mother’s sister, is fighting the same opponent now.

“It’s a terrible thing,” Pierson says, “and there’s nothing that you can do about it.”

The tragedies that have hit her family are horrific enough on their own. Pierson, though, has had to experience the helplessness from another side, this time her best friend from her home, also outside of Boston. Her name is Caroline Deneen, and her fight has been against osteosarcoma, or bone cancer. She, too, currently has the upper hand in the battle.

“We’ve always connected best talking about feelings, thoughts, anxieties,” Summer says. “It’s backwards almost. This massive thing happened to her, and there we were, talking about what’s going on with boys and things like that.”

Caroline was new to the Rivers School for ninth grade, and she and Summer immediately hit it off. They’d talk about anything and everything, and they quickly became so close that they shared with each other the mental health struggles they were facing.

“She can talk to anyone really easily,” Summer says. “I’m not always the biggest talker. We’d hang out a lot. The first time we hung out, we were trying to catch grapes in our mouths.”

While Pierson was a college soccer prospect, it was much different for her friend Caroline, who played on the jayvee team for a while. Sports did not come easily to her. She had been born with a clubfoot, which meant that one of her feet pointed inward and down. She had surgery after surgery to try to correct the problem.

“She was always in a boot,” Pierson says. “At one point, they noticed swelling in her other foot, and it turned out to be a tumor.”

The diagnosis was made in September 2021, right at the start of their senior year of high school. Caroline spent most of that senior year in and out of the hospital, and when she was home, she couldn’t really do much of anything.

“I’d go into school every day and not see her and know what she was going through,” she says. “She was going through hell in a hospital right at that moment. We would go and bring her things and play games with her. The scariest part was at the start, when there was still a chance it had spread to her lungs, which would have been really bad. From September through November, she had a lot of uncertainties.”

Pierson calls her friend “Cara,” not to be confused with the other Cara, whom she calls “Texas,” because, well, she was originally from Texas. The three would spend hours together in Cara’s room, talking, keeping her updated on what was going on at school and playing Super Mario Bros, a game at which Pierson says Cara became “weirdly good. Like unbeatable.”

The enormity of the unfairness that her friend faced, coupled with the helplessness, were overwhelming — and yet, at the same time, it only made their bond stronger. Look no further than what happened on Nov. 15 of that year.

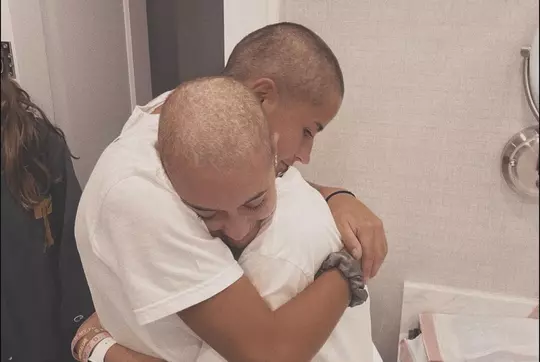

Pierson’s hair is braided behind her, extending down below her shoulders. It is pulled back, away from her eyes. There are pictures she shows me of her from high school where her hair is straight and down to the middle of her back. Her hair in her picture on the Princeton women’s soccer webpage is thick and below her shoulders.

There is another picture on her phone that she shows me, and this one has a much different look to it. In fact, it’s hard to tell who she is at all. There are two people. Both wear white t-shirts. Both have hair that has been buzzed. Which one is Pierson?

“As soon as she started having chemo, her hair started thinning,” Summer says. “It happened really quickly. So we decided we’d shave our heads together, and we did. It was on Nov. 15.”

In the days leading up to Nov. 15, knowing that she was going to shave her head, Pierson started to dye her hair all sorts of colors. It was half pink when it was all cut off.

“We did it, and then another friend did it too,” she says. “The three of us were bald. Cara’s hair didn’t grow back for a year, an entire year, while she was on chemo. We shaved ours again a few weeks after the first time. It’s pretty funny not having hair in the winter in Boston. Eventually, she got really nice wigs that she’d always wear. We had buzz cuts. She had hair.”

Pierson is laughing now as she tells the story. Then she gets silent for a few moments. She is clearly processing and thinking about what to say next. For someone who thinks she’s not good at this speaking thing, it turns out she’s awfully good at it.

“It was great to be with Cara and see her pretty much every day,” Summer says. “We got to be bald together for a little bit, right? But you know what? It was good for me. It took my mind off the artificial things in high school, how I looked, things like that. It gave me a reason to talk to Caroline a lot. If you think about it, it was good, even if it was really bad.”

Caroline Deneen had major surgery and chemo treatments and made it through all of those challenges to hear the one word that every cancer patient dreams of hearing: Remission. It’s even better than the phrases they often hope to start with, phrases like “caught early” and “treatable form.” Her hair grew back, just like that of her friends. She still faces bone scans every six months, and she has big scars where bones had to be removed, not to mention the problems with her clubfoot.

Today she is a student at Villanova. She and Pierson are still very close. How could they not be after all of that?

The Stanhope steps face out to Nassau Hall, and on a perfect Sunday morning, I lost track of how many people stopped to take pictures in front of the building, or on the Tigers that guard it. Holiday cards are being envisioned right in front of my eyes.

Before Summer arrived, I saw a couple with a young son and younger daughter. They took their kids’ picture on the Tigers, and I told them that I have that same picture of my own two when they were roughly that age and that they’d cherish the picture they’d just taken forever, just like I do.

It was a few minutes before noon as all this was happening. I was waiting for the three women’s soccer players to come so I could take their picture. I asked them to hold up a photo on their phone while I did — Esme of her mother, Ally of her father, Summer of her friend.

As I waited, my mind took me back to the conversations I’d had with them. I thought of how Ally said her dad would bring up the tie at her wedding. Wouldn’t that be a special moment? “He’ll get there,” I thought. “He has to be a pretty tough dude to do what he’s done so far.”

I think of Summer’s half-pink hair, disappearing onto the ground, a gesture of love for a friend for whom she would gladly go the rest of her life without having it grow back if it meant that Cara would stay healthy. I think of Esme, alone in her mother’s New York City apartment, trying to balance the unbalanceable for anyone, let alone a 16 year old. And I think of how she writes “Mom” on her wristbands and how, like me, she’ll always draw on her mother’s strength, dignity and love.

At the same time, there’s the picture of my kids outside of Nassau Hall when they were little, and the never-to-go-away knowledge that my mother never had a chance to meet them. What would that have been like? She’d have turned 85 on Nov. 6. What kind of grandmother would she have been? What would she have said to me through my own ups and downs? I can imagine. I can still hear her voice. But I’ll never really know.

I thought about Sean Driscoll’s mother, and how much he would have loved to have her around, just a little longer, just to see him coach that next game, knowing the joy it would bring her to know that she was right all along, that he did have her capacity to want to help people just like she did and that she had reminded him of that. I wish I could have met her, talked to her. Could she be at the next game? Any game? I was immediately struck by the sadness that sadly, she never will.

I could see Ally on her way to the picture, and I was taken back to the diner with her. Like Esme, Ally had a huge bruise, this one on her thigh. You could almost make out the imprint of a soccer ball. I asked her, like I’d asked Esme, if it hurt.

She looked down and said “Yes, a lot at first. It’s not too bad now.”

“Was it in a game?” I asked her.

“Oh no,” she says, “it was from Esme in practice.”

I laughed out loud as she said that.

And I knew that somewhere, maybe in another world, or maybe just in the deepest recesses of her daughter’s mind, that Kaari was laughing too.

— by Jerry Price

.png&width=24&type=webp)