Princeton University Athletics

Black History Month Feature: Marc Ross ’95

February 10, 2022 | Football

Marc Ross is not a flashy guy. He’s an impressive guy. He’s a smart guy – but he’s not a flashy guy. He’s sharp, quick-witted and a great communicator. When he speaks, his sentences never contain an “um” or a “you know” or a “like” that is used as a speed bump of a thought.

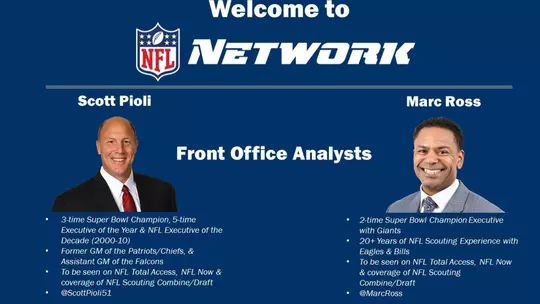

Perhaps it’s because of what he does for a living, or at least half of a living. You might recognize him from his work on the NFL Network, where his analysis is thoughtful, informed and well-presented.

In the league’s current climate, though, perhaps it’s more inciteful to speak about what he does not do for a living. He is not an NFL general manager. He is instead combining his work with the NFL Network with a position as the head of operations for the rebuilt XFL, which will be relaunching – minus the gimmickry of its first two incarnations – a year from now.

“This is the best of both worlds for me,” he says. “I have the stability of the network and the excitement of building something new with the XFL.”

What he hasn’t had is a chance to run an NFL franchise. He has the resume, that’s for sure. If he was actually flashy, he might wear his two Super Bowl rings around, something he says he never, ever does. He has those rings for helping to build the New York Giants into the teams that defeated the New England Patriots after the 2007 and 2011 seasons as the No. 2 person in player evaluation, behind only then-GM Jerry Reese. Before then, his eye for identifying talent helped the Philadelphia Eagles reach multiple NFC championship games and a Super Bowl and made him the team’s Director of College Scouting at age 27. In between Philadelphia and New York, he also spent three years helping the Buffalo Bills rebuild the franchise.

He's interviewed for GM jobs before, but he has not gotten any offers. If you’re Marc Ross, seeing what you see and knowing what you know, it’s easy to look at the obvious. As Black History Month moves along, the talk around the current Super Bowl has to share the spotlight with the recently filed class action lawsuit filed by former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores, which alleges that the league’s owners have engaged in racial discrimination in their hiring practices.

Specifically, there is the Rooney Rule, which requires teams to interview two minority candidates for head coaching and GM positions. For Black candidates, this has led to what they claim are bad faith box-checking meetings, not genuine opportunities.

“Everyone has stories like his,” Ross says. “They’re fact. They’re true. I knew I was going into interviews and that they were sham interviews. If you talk to any Black coach candidate or GM candidate, they’ve been through it, ever since the Rooney Rule started.”

Marc Ross, if you don’t recall, was an All-Ivy League wide receiver and punt returner at Princeton, graduating in 1995. To this day his name is all over the Princeton football record book, including an average of 20.2 yards per catch in 1993 that is still the best in program history. His senior thesis was entitled “Hindrances to Learning in Inner-City Public Schools.”

He certainly has all of the necessary qualifications to be an NFL GM, or at the very least, to have had his opportunity.

“It’s not bitterness,” he says. “Hope is long gone though. If you’re a Black person in this business, you see it and there is that hopelessness. You can see how the game is rigged against you and others, and you can get upset about that. There’s a whole group of guys who feel the same frustrations.”

The issue, he says, lies with the owners.

“The league office, to its credit, has tried, but for all of these initiatives and programs, you’re still talking about 32 billionaires,” he says. They’re going to do whatever they want. You can’t force them to do anything with their teams. They can totally ignore minorities for whatever inherent or unconscious biases they have, and they’re going to keep having these sham interviews. To be a Black head coach, you have to have a laundry list of accomplishments. You see all these White coaches with almost no experience getting head coaching jobs. Black candidates never get that chance. It may seem naïve, but I’ve been part of it. Not one of those owners will say they’re racist or think they are, and I’m not calling anyone anything. But there is something wrong here.”

Ross grew up in Philadelphia, and his college choices came down to Princeton and Penn. It was Steve Verbit, who is still with the program as its Senior Associate Head Coach and Co-Defensive Coordinator, who recruited him.

After playing on the freshman team in 1991, Ross was a member of Princeton’s 1992 Ivy League championship team. He set the yards per reception record as a junior, and his receiving yards and kick return yards still have him among the leaders in all-purpose yardage at Princeton.

“I loved my time at Princeton,” he says. “I was just telling my daughter [Skylar, a high school junior] about it. All of my best friends are from my Princeton years. I grew a lot. I learned a lot. I developed as a person, as a student, as an athlete. It was everything you’d want from your college experience. It all came together for me. Whenever I talk about Princeton or when I go back, I have those feelings all over again.”

When Ross played at Princeton, there were relatively few Black players on the roster. Today, Princeton football has a much more diverse roster.

“It’s remarkable to see the opportunities that Bob has been able to provide,” he says of Bob Surace, the Tiger head coach. “We didn’t have many black kids, and there were less than that before I got there. I’m so proud of what Bob is doing. When I went down there and hung out at practice, I was text the guys from when I was there and say ‘you can’t believe how many Black guys are here now.’ It’s very noticeable. And now with John [Mack, the Ford Family Director of Athletics], for the first time you have a Black AD. I’m so happy for him. I’m rooting so hard for him.”

He began his NFL front office career as an intern with the Eagles in 1997. He worked on his first draft a year later, and the players he would bring in through the years would help the team to NFC title games from 2001-04, with a trip to the Super Bowl after the fourth of those.

After his three years with the Bills, he made the move to the Giants. He was there for the franchise’s two most recent Super Bowl wins, both of which came over the heavily favored Patriots, including the one that spoiled the Pats 18-0 record.

“For the first one, I was sitting with my wife [Pualani],” he says. “I never once cheered. Not after the helmet catch. Not after the winning TD. I was still looking at it like they still had a chance. For the second one, I sat in the press box in a booth. It just doesn’t feel real to win the Super Bowl. You see yourself winning You’re in the parade. You have the trophy. But it always feels like it never really happened. And to be part of two of the best Super Bowls ever played? Winning is amazing, but also being part of monumentally historic Super Bowls as well? That’s incredible.”

By then, he’d shown that he could build a team pretty much any way possible, whether through the draft or by surrounding established stars with the complements they need to win big. With his education, experience, intelligence and personality, he seemed like a natural for a GM job.

And his name came up every time there was an opening. And he got his share of interviews. Each time, a White candidate was hired.

“The owners can always say ‘well, he crushed it on the interview,’” he says. “The reality is that they can just hire whoever they want. Super Bowl rings? Accolades? It doesn’t matter. No matter what happens, with whatever the pressure comes up, it’s the 32 owners. You can make speeches. You can put stickers on helmets. Nothing ever changes.”

When the Giants fortunes began to turn, there were two front office members who were let go – Reese, who is also Black, and Ross.

“When Jerry got fired, I was the only other who also got fired,” he says. “We weren’t the only two people there. Everything we did was collaborative. There are still plenty of people there who were there before me, who were there with me and who are still there.”

He has rebounded well with the job on the NFL Network, where his football knowledge is obvious. And now he has the opportunity with the new XFL.

“My role is to figure out why league has failed before and to show what you need to do to put a quality product on the field,” he says. “The Rock has taken over as the owner of the league. Everyone involved is passionate about it. We’ve gotten the cities together. I’m working on the football decisions, with the business team, the marketing team and the ownership.”

As he does all of this, and as he keeps his focus on what happens on the field in the NFL, he will be watching what happens with Flores and his lawsuit with a bit more interest than most.

“To be honest, the lawsuit is long overdue,” he says. “He has a lot of courage to do this, knowing that by doing so his career is basically over. It’s important though. Black candidates just want a chance.”

— by Jerry Price

.png&width=24&type=webp)