Princeton University Athletics

Black History Month Feature Story: The Honorable Roger Gordon

February 23, 2023 | Men's Basketball

The view from the balcony, any balcony, is expansive. From here you can see everything. No one is out of your line of sight. And so it is that Roger Gordon, Princeton men’s basketball Class of 1973, has just come into view as he makes his way up to, in this case, the balcony of Jadwin Gym.

He stops several times to say hello, maybe to someone he knows, maybe to someone he doesn’t. It doesn’t make a difference. He’ll talk to anyone, at any time.

He is moving slowly, as he always does these days. He moves slowly, but purposefully. It’s the judge in him, perhaps. Or maybe it’s just the sum of all of experiences, not just his years on the bench.

Finally he has made his way to Section 209, Row 12. A bit out of breath, the 71-year-old Gordon settles into Seat 6. Out in front of him, Princeton is playing a men’s basketball game. He lets out an audible “Woah” at a Keyshawn Kellman finish.

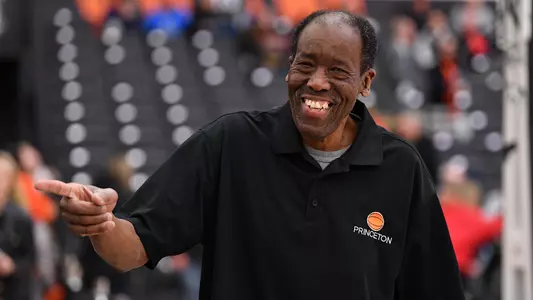

He’s a humble man, to be sure. Humble, and sincere. His smile seems to be permanently affixed to his face. When he asks how you’re doing, he really wants to know. His handshake almost always comes with his left arm around you. He carries with him an unmistakable vibe of positivity, and that vibe is infectious.

“Mention the name Roger Gordon to any Princeton men’s basketball player in the last 40 years,” says Princeton head coach Mitch Henderson, “and a smile will come across every single face.”

As he looks out at the game, he reluctantly talks about his life as a Philly guy through and through, other than all of the time he has spent connected to Princeton. He talks about his upbringing, the city to which he continues to give so much, how he chose Princeton in the first place, what the men’s basketball program means to him.

“It’s been 54 years of Princeton basketball,” he says. “I’ve had every role you can have in the program except for head coach. I’m so proud to have been a part of this.”

He also talks about being able to relax up here in the balcony, how he can put his feet up, take a deep breath and take it all in. There’s a great irony to all of this, of course, because of one obvious reason.

The balcony is no place for Roger Gordon.

This is a place from which to observe, and from a distance at that. That’s not who Roger Gordon is. He needs to be much closer to where it’s all going on. He needs to get his hands dirty. He can’t do that from Section 209.

“Roger is one of those people where everything he touches, he makes better,” says former Tiger player and coach John Thompson III, who goes back with Gordon to the 1980s. “Just having him around keeps you grounded. There’s nothing he wouldn’t do for you, for the program and for anyone really, and he asks for nothing in return. There aren’t a lot of people you meet who have that quality.”

It's not easy to get Gordon to talk about himself. Even when he does, it’s usually it terms of other people, those he’s helped, especially those who don’t realize how much he’s helped them. When he does stay focused on his own story, he tells the remarkable tale in such a matter-of-fact way that it’s easy to forget all of the amazing moments in his life.

He goes through, for instance, his career path, as if it’s something anyone could have done.

“I was a public defender for seven years,” he says. “I was a DA for two. I was a city lawyer for two years. I was a civil plaintiffs attorney for two years. I was an insurance lawyer defensive civil attorney for 12 years. I was a judge off and on from 2009 through 2018.”

Down on the court, Tosan Eubuomwan has found an open Zach Martini, who drills a three-pointer. From his seat Gordon probably doesn’t even notice the barely audible “yeah” that slips out from his mouth. Then he’s back to his legal career and finishes with this:

“Guess I couldn’t keep a job.”

As he laughs, it's clear that what he’s done is point out something very special about himself, whether he meant to or not. If you look at his career, he’s spent way more time with the underdog than with the favorite. That’s who he is. He’s the one looking out for the ones who need it most.

“Roger is completely selfless,” Henderson says. “Roger is always there to give his time and strength and support to others. He sends me positive notes and leaves voicemails of encouragement. I have learned and continue to learn and grow so much because of Roger. He is a star of a human being.”

In his few minutes in the balcony he couldn’t possibly list all of the causes he’s worked for in Philadelphia, all of which are geared towards helping the young people he’s seen his whole life in that city who didn’t have the kind of hope he did. He brings kids from West Philadelphia up to Princeton to see what college looks like. He is a driving force in the Major League Baseball RBI program, which stands for “Reviving Baseball In Inner Cities.” He has coached baseball for nearly 60 years.

“It’s deeper than just getting more black kids to play baseball,” he says. “It’s about getting kids to look more than a week down the road. It’s about getting them to look five years down the road. Do you want to be 18 years old, 20 years old, with two kids? Do you want to be the 21-year-old father with three kids and three different mothers? That’s a difficult life. Those are decisions that change your life forever. We’re trying to get teenage girls to play softball and not end up pregnant. We want them to have choices for a better life. And it all starts with education.”

He knows all about what sports and education can do for an inner city Black kid. He grew up in the Germantown section of Philadelphia, the only child of a social worker father and teacher mother. He also saw what discrimination could do.

“Back then, all the Philly public schools would close down for lunch,” he says. “They assumed everyone would go home for lunch and then come back for the second part of the day. Every school in the city closed during lunchtime. My parents both worked, and they wanted to put me somewhere that I could be all day. My parents were from the South. They both had an accent. When they came to the door at Germantown Academy in 1956, they were told that they weren’t allowing Black kids.”

Instead, he ended up at Penn Charter, where he stayed from Kindergarten through 12th grade.

“My parents stressed education,” he says. “There was a sad disparity between the education that I got and the education that the guys I grew up with who weren’t as fortunate got with the public schools. I see it now still. Black kids, Spanish kids. There are a lot of people who don’t have access to good education, or don’t value education, and they end up having difficult lives because of it.”

In addition to being a serious student, Gordon was also a standout athlete, in baseball and basketball. He’d go to the Palestra back when there were Big Five doubleheaders all season and the building would be packed (by the way, he hasn’t missed a Princeton-Penn game at the Palestra in more than 50 years).

He would be recruited by Penn when Dick Harter was the head coach.

“I knew they had a 6-7 guard named Corky Calhoun who was coming in,” Gordon said. “I told Coach Harter ‘I’m a 6-2 center. How am I ever going to play?’”

Joe Heiser, a 1968 Princeton grad who was part of Butch van Breda Kolff’s final two Princeton teams and then Pete Carril’s first, saw Gordon and mentioned him to the new coach. Gordon came to Princeton on his own, figuring he might try baseball, since he was unlikely to make an impact in basketball.

Instead, he became a manager of the basketball team — until Carril saw him shooting around one day.

“He said to me ‘who are you?’ and I said ‘Gordon, team manager,’” he says. “Then Coach said ‘make a few more jumpers and you’ll be on the team,’ so I stepped back and made three more.”

He’d end up as part of a 17-0 freshman team that featured Brian Taylor and Ted Manakas. He’d score 12 points as a varsity player and then head to Seton Hall for law school after a brief stay on Carril’s coaching staff, where he became the first Black assistant coach in Ivy men’s basketball history. He’s also served in the leadership of the Friends of Princeton Basketball, including as interim president at times.

Even today, on game nights, he’s one of the first people in the building, several hours before tip. You can find him on the court before and after games, setting up and retrieving the balls, encouraging the players, doing anything he can to help out. And he talks. To anyone and everyone. He has been an advisor, a friend, a calming influence and a loyal supporter of every player and coach who has come through in his 54 years.

“I still see people who would come to games in Dillon Gym,” says Gordon, who has two children of his own, a son who is a Philly truck driver and a daughter headed to medical school. “I say hi to them. I meet their kids and grandkids. I love to still be around here.”

As he sits in the balcony, he’s getting antsy. You can tell he wants to get back down to his normal spot, behind the bench. Before he goes, he notices the picture of Carril that now hangs on the seat where the late coach used to watch games, in the last row of the balcony, one section over.

“Pete would say he was my biggest influence,” Gordon says. “He’d always say that there was a way to solve any problem. It might not be visible at first, but there is always a way to solve a problem, so shut up and get on it.”

He laughs. Of course he does. As he tells the story, it’s hardly a stretch to picture those words as they came from Carril.

“So what do you do to solve a problem?” Gordon asks rhetorically. “That’s the effect he had on us. Solve the problem. Get involved. When I bring kids up to Princeton, when I bring West Philly kids up, they get to see what college is about. They see the kids with the books. When [Princeton baseball coach] Scott Bradley comes down with his coaches, the kids get to see what their life can be if they think ahead. It’s hard to get kids to think that way, but you always keep trying.”

And with that, he’s gone. The game continues, and he makes his way down to the railing and then into the entryway. In a few seconds, he has reemerged, now on the court. Now he walks back to the bench, into the action, around the people.

From the balcony, it’s easy to see that he is at home.

— by Jerry Price